SortedMap

| Operations | Average | Worst Case |

|---|---|---|

| Space | O(n) | O(n) |

| Insert | O(1) | O(n) |

| Lookup | O(1) | O(n) |

| Delete | O(1) | O(n) |

Useful Sites

- Справочник по Java Collections Framework

- Differences between HashMap, HashTable, LinkedHashMap and TreeMap in java

- How HashTable works Internally? HashTable vs HashMap in Java - By Naveen AutomationLabs (VIDEO-EN)

- How HashMap works internally || Popular java interview question on collection (VIDEO-EN)

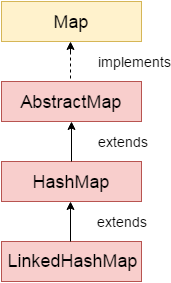

public class LinkedHashMap<K,V> extends HashMap<K,V> implements Map<K,V> import java.util.*;

class LinkedHashMap1{

public static void main(String args[]){

LinkedHashMap<Integer,String> hm=new LinkedHashMap<Integer,String>();

hm.put(100,"Amit");

hm.put(101,"Vijay");

hm.put(102,"Rahul");

for(Map.Entry m:hm.entrySet()){

System.out.println(m.getKey()+" "+m.getValue());

}

}

} Output:100 Amit

101 Vijay

102 Rahul

TreeMap guarantees log(n) time cost for operatons like containsKey, get, put and remove.

Useful Sites

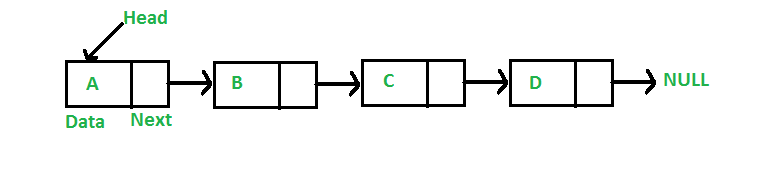

- Linked lists are preferable over arrays when:

- you need constant-time insertions/deletions from the list (such as in real-time computing where time predictability is absolutely critical)

- you don't know how many items will be in the list. With arrays, you may need to re-declare and copy memory if the array grows too big

- you don't need random access to any elements

- you want to be able to insert items in the middle of the list (such as a priority queue)

- Arrays are preferable when:

- you need indexed/random access to elements

- you know the number of elements in the array ahead of time so that you can allocate the correct amount of memory for the array

- you need speed when iterating through all the elements in sequence. You can use pointer math on the array to access each element, whereas you need to lookup the node based on the pointer for each element in linked list, which may result in page faults which may result in performance hits.

- memory is a concern. Filled arrays take up less memory than linked lists. Each element in the array is just the data. Each linked list node requires the data as well as one (or more) pointers to the other elements in the linked list.

Array Lists (like those in .Net) give you the benefits of arrays, but dynamically allocate resources for you so that you don't need to worry too much about list size and you can delete items at any index without any effort or re-shuffling elements around. Performance-wise, arraylists are slower than raw arrays.

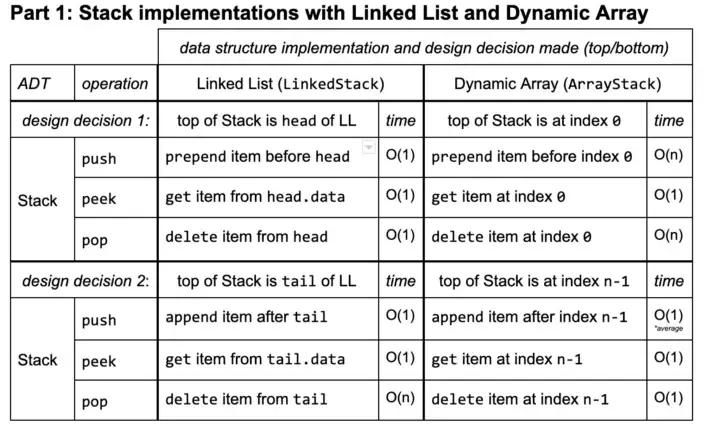

First, we will talk about stacks. A Stack is a linear data structure that is very similar to a list because it stores items in an order, but you can only access to an item at the top. One example in the real world is when you press Command + Z and Command + Y on Mac or Control + Z and Control + Y on Microsoft to undo and redo something, in both cases you are only going to have access to the last change you have made. Another demonstration of a stack would be when you try to go backward or forward on the browser. Furthermore, a Stack is an abstract data type, but it could also be implemented using concrete data structures like Dynamic Arrays and Linked Lists.

It uses the following operations:

- pop(): Remove the top item from the stack.

- push( item) : Add an item to the top of the stack.

- peek ( ): Return the top of the stack.

- isEmpty() : Return true if and only if the stack is empty. Unlike an array, a stack does not offer constant-time access to the it h item. However, it does allow constanttime adds and removes, as it doesn't require shifting elements around.

class Stack

{

private int arr[];

private int top;

private int capacity;

// Constructor to initialize the stack

Stack(int size)

{

arr = new int[size];

capacity = size;

top = -1;

}

// Utility function to add an element `x` to the stack

public void push(int x)

{

if (isFull())

{

System.out.println("Overflow\nProgram Terminated\n");

System.exit(-1);

}

System.out.println("Inserting " + x);

arr[++top] = x;

}

// Utility function to pop a top element from the stack

public int pop()

{

// check for stack underflow

if (isEmpty())

{

System.out.println("Underflow\nProgram Terminated");

System.exit(-1);

}

System.out.println("Removing " + peek());

// decrease stack size by 1 and (optionally) return the popped element

return arr[top--];

}

// Utility function to return the top element of the stack

public int peek()

{

if (!isEmpty())

return arr[top];

else

System.exit(-1);

return -1;

}

// Utility function to return the size of the stack

public int size() {

return top + 1;

}

// Utility function to check if the stack is empty or not

public boolean isEmpty() {

return top == -1; // or return size() == 0;

}

// Utility function to check if the stack is full or not

public boolean isFull() {

return top == capacity - 1; // or return size() == capacity;

}

}

class Main

{

public static void main (String[] args)

{

Stack stack = new Stack(3);

stack.push(1); // inserting 1 in the stack

stack.push(2); // inserting 2 in the stack

stack.pop(); // removing the top element (2)

stack.pop(); // removing the top element (1)

stack.push(3); // inserting 3 in the stack

System.out.println("The top element is " + stack.peek());

System.out.println("The stack size is " + stack.size());

stack.pop(); // removing the top element (3)

// check if the stack is empty

if (stack.isEmpty())

System.out.println("The stack is empty");

else

System.out.println("The stack is not empty");

}

}Output:

Inserting 1

Inserting 2

Removing 2

Removing 1

Inserting 3

The top element is 3

The stack size is 1

Removing 3

The stack is empty

One case where stacks are often useful is in certain recursive algorithms. Sometimes you need to push temporary data onto a stack as you recurse, but then remove them as you backtrack (for example, because the recursive check failed). A stack offers an intuitive way to do this. A stack can also be used to implement a recursive algorithm iteratively. (This is a good exercise! Take a simple recursive algorithm and implement it iteratively.)

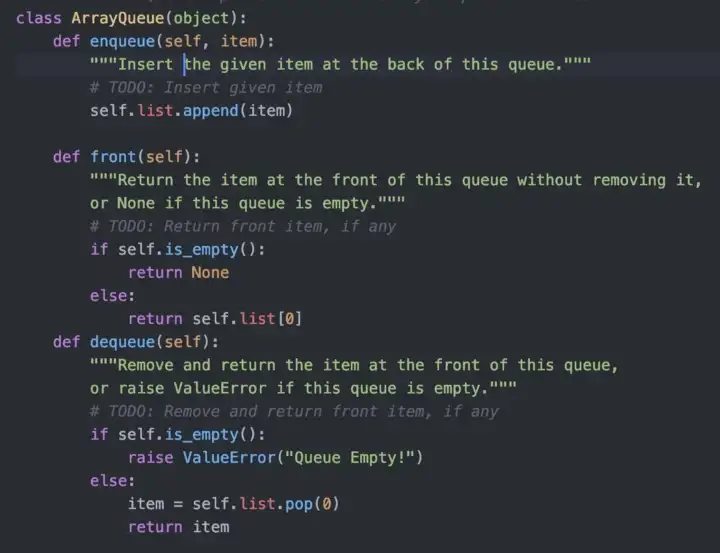

A queue implements FIFO (first-in first-out) ordering. As in a line or queue at a ticket stand, items are

removed from the data structure in the same order that they are added.

Unlike stacks, in a Queue, the last item to get in will be the last to get out and the first item that got in will be the first to get out. Some applications of a queue in the real world are scheduling systems, networking and handling congestion, multiplayer gaming, interview questions, music, etc. A Queue is an abstract data type, but it could also be implemented using concrete data structures like Dynamic Arrays and Linked Lists.

It uses the operations:

- add (item) : Add an item to the end of the list.

- remove(): Remove the first item in the list.

- peek(): Return the top of the queue.

- isEmpty() : Return true if and only if the queue is empty. Queue

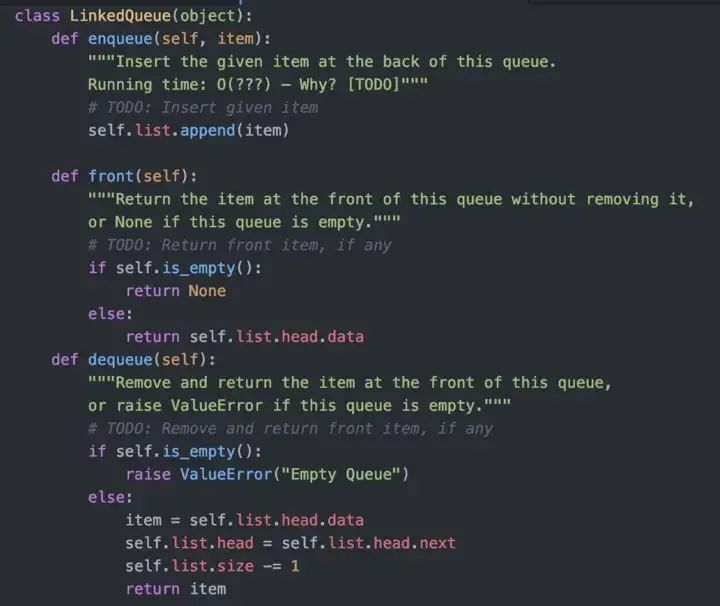

Below is the code for the methods of a Queue

Queue in a linked list

Usefull sites

Many interviewees find tree and graph problems to be some of the trickiest. Searching a tree is more

complicated than searching in a linearly organized data structure such as an array or linked list. Additionally, the worst case and average case time may vary wildly, and we must evaluate both aspects of any

algorithm. Fluency in implementing a tree or graph from scratch will prove essential.

Because most people are more familiar with trees than graphs (and they're a bit simpler), we'll discuss trees

first. This is a bit out of order though, as a tree is actually a type of graph.

A nice way to understand a tree is with a recursive explanation, A tree is a data structure composed of nodes,

- Each tree has a root node, (Actually, this isn't strictly necessary in graph theory, but it's usually how we use trees in programming, and especially programming interviews.)

- The root node has 2ero or more child nodes.

- Each child node has zero or more child nodes, and so on.

The tree cannot contain cycles. The nodes mayor may not be in a particular order, they could have any data

type as values, and they may or may not have links back to their parent nodes.

A very simple class definition for Node is:

class Node {

public String name;

public Node[] children;

} You might also have a Tree class to wrap this node. For the purposes of interview questions, we typically do not use a Tre e class. You can if you feel it makes your code simpler or better, but it rarely does.

class Tree {

publi c Node root ;

} A binary tree is a tree in which each node has up to two children. Not all trees are binary trees. For example,

this tree is not a binary tree. You could call it a ternary tree.

A node is called a "leaf" node if it has no children.

A binary search tree is a binary tree in which every node fits a specific ordering property: al l lef t

descendents <= n < all righ t descendents. This must be true for each node n.

The definition of a binary search tree can vary slightly with respect to equality. Under some definitions, the tree cannot have duplicate values. In others, the duplicate values will be on the right

or can be on either side. All are valid definitions, but you should clarify this with your interviewer.

While many trees are balanced, not all are. Ask your interviewer for clarification here. Note that balancing a

tree does not mean the left and right subtrees are exactly the same size (like you see under "perfect binary

trees" in the following diagram).

A tree is actually a type of graph, but not all graphs are trees. Simply put, a tree is a connected graph without

cycles.

A graph is simply a collection of nodes with edges between (some of) them.

- Graphs can be either directed (like the following graph) or undirected. While directed edges are like a one-way street, undirected edges are like a two-way street.

- The graph might consist of multiple isolated subgraphs. If there is a path between every pair of vertices, it is called a "connected graph."

- The graph can also have cycles (or not). An "acyclic graph" is one without cycles.

This is the most common way to represent a graph. Every vertex (or node] stores a list of adjacent vertices. In an undirected graph, an edge like (a , b) would be stored twice: once in a's adjacent vertices and once in b s adjacent vertices. A simple class definition for a graph node could look essentially the same as a tree node

class Graph {

publi c Node[] nodes;

}

clas s Node {

public String name;

publi c Node[] children ;

}The Graph class is used because, unlike in a tree, you can't necessarily reach all the nodes from a single node. You don't necessarily need any additional classes to represent a graph. An array (or a hash table) of lists (arrays, array lists, linked lists, etc.) can store the adjacency list. The graph above could be represented as:

6: 1

1: 2

2: 3

3: 2

4: 6

5: 4

6: S

This is a bit more compact, but it isn't quite as clean. We tend to use node classes unless there's a compelling

reason not to.

The same graph algorithms that are used ori adjacency lists (breadth-first search, etc.) can be performed

with adjacency matrices, but they may be somewhat tess efficient. !n the adjacency list representation, you

can easily iterate through the neighbors of a node. In the adjacency matrix representation, you will need to

iterate through all the nodes to identify a node's neighbors.

- Graph Search

The two most common ways to search a graph are depth-first search and breadth-first search. In depth-first search (DFS), we start at the root (or another arbitrarily selected node) and explore each branch completely before moving on to the next branch. That is, we go deep first (hence the name depthfirst search) before we go wide. In breadth-first search (BFS), we start at the root (or another arbitrarily selected node) and explore each neighbor before going on to any of their children. That is, we go wide (hence breadth-first search) before we go deep. See the below depiction of a graph and its depth-first and breadth-first search (assuming neighbors are iterated in numerical order).

Breadth-first search and depth-first search tend to be used in different scenarios. DFS is often preferred if we

want to visit every node in the graph. Both will work just fine, but depth-first search is a bit simpler.

However, if we want to find the shortest path (or just any path) between two nodes, 8FS is generally better.

Consider representing all the friendships in the entire worid in a graph and trying to find a path of friendships between Ash and Vanessa.

In depth-first search, we could take a path like Ash -> Bria n -> Carleto n -> Davi s -> Eri c

-> Farah -> Gayle -> Harr y -> Isabell a -> Dohn -> Kari... and then find ourselves very

far away. We could go through most of the world without realizing that, in fact, Vanessa is Ash's friend. We

will still eventually find the path, but it may take a long time. It also won't find us the shortest path.

Adjacency List representation in Java

import java.util.*;

class Graph {

// A utility function to add an edge in an

// undirected graph

static void addEdge(ArrayList<ArrayList<Integer> > adj,

int u, int v)

{

adj.get(u).add(v);

adj.get(v).add(u);

}

// A utility function to print the adjacency list

// representation of graph

static void

printGraph(ArrayList<ArrayList<Integer> > adj)

{

for (int i = 0; i < adj.size(); i++) {

System.out.println("\nAdjacency list of vertex"

+ i);

System.out.print("head");

for (int j = 0; j < adj.get(i).size(); j++) {

System.out.print(" -> "

+ adj.get(i).get(j));

}

System.out.println();

}

}

// Driver Code

public static void main(String[] args)

{

// Creating a graph with 5 vertices

int V = 5;

ArrayList<ArrayList<Integer> > adj

= new ArrayList<ArrayList<Integer> >(V);

for (int i = 0; i < V; i++)

adj.add(new ArrayList<Integer>());

// Adding edges one by one

addEdge(adj, 0, 1);

addEdge(adj, 0, 4);

addEdge(adj, 1, 2);

addEdge(adj, 1, 3);

addEdge(adj, 1, 4);

addEdge(adj, 2, 3);

addEdge(adj, 3, 4);

printGraph(adj);

}

} Adjacency list of vertex 0

head -> 1-> 4

Adjacency list of vertex 1

head -> 0-> 2-> 3-> 4

Adjacency list of vertex 2

head -> 1-> 3

Adjacency list of vertex 3

head -> 1-> 2-> 4

Adjacency list of vertex 4

head -> 0-> 1-> 3

Adjacency Matrix representation in Java

// Adjacency Matrix representation in Java

public class Graph {

private boolean adjMatrix[][];

private int numVertices;

// Initialize the matrix

public Graph(int numVertices) {

this.numVertices = numVertices;

adjMatrix = new boolean[numVertices][numVertices];

}

// Add edges

public void addEdge(int i, int j) {

adjMatrix[i][j] = true;

adjMatrix[j][i] = true;

}

// Remove edges

public void removeEdge(int i, int j) {

adjMatrix[i][j] = false;

adjMatrix[j][i] = false;

}

// Print the matrix

public String toString() {

StringBuilder s = new StringBuilder();

for (int i = 0; i < numVertices; i++) {

s.append(i + ": ");

for (boolean j : adjMatrix[i]) {

s.append((j ? 1 : 0) + " ");

}

s.append("\n");

}

return s.toString();

}

public static void main(String args[]) {

Graph g = new Graph(4);

g.addEdge(0, 1);

g.addEdge(0, 2);

g.addEdge(1, 2);

g.addEdge(2, 0);

g.addEdge(2, 3);

System.out.print(g.toString());

}

}- Threes & Graphs

Depth-First Search (DFS)

In DFS, we visit a node a and then iterate through each of a's neighbors. When visiting a node b that is a

neighbor of a, we visit all of b's neighbors before going on to a's other neighbors. That is, a exhaustively

searches b's branch before any of its other neighbors.

Note that pre-order and other forms of tree traversal are a form of DFS. The key difference is that when

implementing this algorithm for a graph, we must check if the node has been visited. If we don't, we risk

getting stuck in an infinite loop.

The pseudocode below implements DFS.

void search(Node root) {

if (roo t == null ) return ;

visit(root) ;

root.visite d = true ;

foreach (Node n in root.adjacent) {

if (n.visited == false ) {

search(n);

}

}

}Breadth-First Search (BFS)

BFS is a bit less intuitive, and many interviewees struggle with the implementation unless they are already familiar with it. The main tripping point is the (false) assumption that BFS is recursive. It's not. Instead, it uses a queue. In BFS, node a visits each of a's neighbors before visiting any of their neighbors. You can think of this as searching level by level out from a. An iterative solution involving a queue usually works best,

void search(Node root) {

Queue queue = new Queue();

root.marked = true ;

queue.enqueue(root); // Add to the end of queue

while (Iqueue.isEmptyO) {

Node r « queue.dequeue(); // Remove from the fron t of the queue

visit(r) ;

foreach (Node n in r.adjacent) {

if (n.marked == false ) {

n.marked = true ;

queue.enqueue(n);

}

}

}

} If you are asked to implement BFS, the key thing to remember is the use of the queue. The rest of the algorithm flows from this fact.

Understanding implementation

public static void bubbleSort(int [] sort_arr, int len){

for (int i=0;i<len-1;++i)

for(int j=0;j<len-i-1; ++j)

if(sort_arr[j+1]<sort_arr[j]) {

int swap = sort_arr[j];

sort_arr[j] = sort_arr[j+1];

sort_arr[j+1] = swap;

}

}-

The first step is to create a method,

bubbleSort, that takes the array as the input to be sorted,sort_arr, and thelengthof the array,len, as seen on line 3 in the code above. -

The second step is to create an outer for loop which will iterate over each element of the array as shown on line 5.

-

The third step is to create an inner for loop as shown on line 7. This

forloop starts from the first element of the array till the second lastindex,(len - i - 1). -

Each time one index less than the last is traversed as at the end of each iteration, the largest element for that iteration reaches the end. Within the nested for loop is the if condition from lines 9 to 15. This checks that if the element on the left is greater than that on the right. If so, it swaps the two elements.

Note: The outer loop will iterate over all elements in the array even if the array is already completely sorted

Time Complexity

Since there are two nested loops within the algorithm, the time complexity will be O(n^2) where n is equivalent to the length of the array to be sorted.

O(n^2) average and worst case. Memory - 0(1).

Selection sort is the child's algorithm: simple, but inefficient. Find the smallest element using a linear scan and move it to the front (swapping it with the front element). Then, find the second smallest and move it, again doing a linear scan. Continue doing this until all the elements are in place

void sort(int arr[]) {

int n = arr.length;

// One by one move boundary of unsorted subarray

for (int i = 0; i < n-1; i++)

{

// Find the minimum element in unsorted array

int min_idx = i;

for (int j = i+1; j < n; j++)

if (arr[j] < arr[min_idx])

min_idx = j;

// Swap the found minimum element with the first

// element

int temp = arr[min_idx];

arr[min_idx] = arr[i];

arr[i] = temp;

}

}Runtime: 0( n log(n) ) average and worst case. Memory: Depends.

Merge sort divides the array in half, sorts each of those halves, and then merges them back together. Each of those halves has the same sorting algorithm applied to it. Eventually, you are merging just two single element arrays. It is the "merge" part that does all the heavy lifting.

public static void mergeSort(int[] a, int n) {

if (n < 2)

return;

int mid = n / 2;

int[] l = new int[mid];

int[] r = new int[n - mid];

for (int i = 0; i < mid; i++)

l[i] = a[i];

for (int i = mid; i < n; i++)

r[i - mid] = a[i];

mergeSort(l, mid);

mergeSort(r, n - mid);

merge(a, l, r, mid, n - mid);

}public static void merge (

int[] a, int[] l, int[] r, int left, int right) {

int i = 0, j = 0, k = 0;

while (i < left && j < right) {

if (l[i] <= r[j])

a[k++] = l[i++];

else

a[k++] = r[j++];

}

while (i < left)

a[k++] = l[i++];

while (j < right)

a[k++] = r[j++];

}

.png)

.jpg)