-

-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 604

Managing Memory Pages

During boot time, mempool.cc runs arch_setup_free_memory. Using e820 interrupt, the OS asks the BIOS for all valid memory addresses. It would setup the MMU to map all pages, up to 1Gb to their physical counterparts, and mark those pages as free, with mmu::free_initial_memory_range. Now OSv can use new to allocate memory. The rest of arch_setup_free_memory contains custom memory mapping, to aid malloc with more efficient allocation. Since it's not related directly to pages allocation - I won't discuss this part.

What does free_initial_memory_range do? Eventually, it adds the free memory range to an intrusive red-black tree. What does intrusive means? In regular C++ set<Foo>, the data in the red-black tree is external to the tree. There are tree nodes with their pointers, and they contain the int data. A typical node in a red-black tree looks like

struct node {

node *left, *right;

Color color;

Foo data;

}

An intrusive set would have the left and right pointers contains in the Foo struct.

struct Foo {

Foo *left, *right;

Color color;

int fooBar, fooBaz;

}

A typical implementation of intrusive linked list can be found in the linux kernel.

In our case, each free memory range header would contain pointers to the descendant nodes in the red-black-tree. The initialization code would eventually add a free range to the set, by initializing the free page object at the beginning of the page, and then adding it to the set, uniting two adjacent ranges if possible

new (addr) page_range(size);

free_page_range(static_cast<page_range*>(addr));

...

free_page_ranges.insert(*range);

merge(&*i, &*boost::next(i));

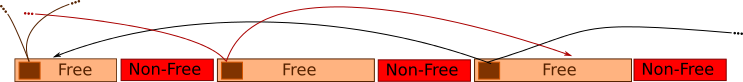

So at the end of the day, after the system boots, we have a red-black-tree that looks like this:

Each brown rectangle is a free memory range. The small dark brown rectangle is the header at the beginning of each range, which points to two other descendant ranges. Since free ranges are ordered by their physical address, each free range would point to one range in a higher address, and one range at a lower address.

How can we see that in action? Luckily, the OSv folks have written a gdb macro that prints the contents of free_page_ranges. Let's run an OSv instance, and break at memory::setup:

$ ./script/run.py -d

# in a different terminal

$ echo

$ gdb ./build/debug/loader.elf

(gdb) connect # OSv macro that connects to local target

...

(gdb) hbr memory::setup()

Hardware assisted breakpoint 1 at 0x392e33: file /home/elazar/dev/osv/core/mempool.cc, line 1060.

(gdb) monitor system_reset

(gdb) continue

Continuing.

Breakpoint 1, memory::setup () at /home/elazar/dev/osv/core/mempool.cc:1060

1060 {

(gdb) osv heap

(gdb)

We've stopped executing before calling arch_setup_free_memory, and indeed no free memory ranges are added to the set yet. Let's initialize it:

(gdb) n

1061 arch_setup_free_memory();

(gdb) n

1062 }

(gdb) osv heap

0xffffc00000dde000 0x000000003f211000

0xffffc0003fff0000 0x0000000000001000

0xffffc0003fff2000 0x0000000000003000

0xffffc0003fff7000 0x0000000000001000

0xffffc0003fff9000 0x0000000000001000

0xffffc0003fffb000 0x0000000000001000

0xffffc0003fffd000 0x0000000000001000

0xffffc0003ffff000 0x000000003ffff000

Here are the free ranges registered. Let's allocate a page:

(gdb) p memory::alloc_page()

Cannot remove breakpoints because program is no longer writable.

Further execution is probably impossible.

$1 = (void *) 0xffffc0003ffee008

(gdb) osv heap # base_addr size

0xffffc00000dde000 0x000000003f210000

0xffffc0003fff0000 0x0000000000001000

0xffffc0003fff2000 0x0000000000003000

0xffffc0003fff7000 0x0000000000001000

0xffffc0003fff9000 0x0000000000001000

0xffffc0003fffb000 0x0000000000001000

0xffffc0003fffd000 0x0000000000001000

0xffffc0003ffff000 0x000000003ffff000

Note that the first range's size shrunk from 0x3f211000 to 0x3f210000, by 0x1000=4096=4K.

What happens when someone needs a memory page? The simpler path happens before memory system initialization. One would simply pick up the first free range, decrease it by a page_size, and return this range:

auto begin = free_page_ranges.begin();

auto p = &*begin;

p->size -= page_size;

if (!p->size) {

free_page_ranges.erase(begin);

}

This approach wouldn't scale when multiple CPUs are trying to fetch a free page from the free_page_ranges list. In order to reduce contention, each CPU maintains its own page_buffer. The page buffer, is a simple stack, of up to 512 free pages owned by a particular CPU. When allocating a page, the CPU would take the topmost free page, when free'ing a page, the CPU would add it to the top. No synchronization is needed, since each CPU has its own page buffer.

Let's see that in action. We'll stop OSv after it's loaded

$ gdb build/debug/loader.elf

...

(gdb) connect

...

(gdb) # let's make gdb print small arrays

(gdb) set print elements 2

(gdb) osv percpu memory::page_pool::percpu_l1

CPU 0:

{static max = 512, nr = 248, free = {0xffffc00023e80000, 0xffffc00023e81000...}}

CPU 1:

{static max = 512, nr = 42, free = {0xffffc00037b8a000, 0xffffc00037b8b000...}}

CPU 2:

{static max = 512, nr = 92, free = {0xffffc0003f75b000, 0xffffc0003f75c000...}}

CPU 3:

{static max = 512, nr = 251, free = {0xffffc0003f613000, 0xffffc0003f614000...}}

We can see all the page buffers for all 4 CPUs, which has currently 248, 42, 92 and 251 used pages for each CPU. Let's allocate a page:

(gdb) p memory::alloc_page()

$2 = (void *) 0xffffc000247c6000

(gdb) osv percpu memory::page_pool::percpu_l1

CPU 0:

{static max = 512, nr = 247, free = {0xffffc00023e80000, 0xffffc00023e81000...}}

CPU 1:

{static max = 512, nr = 42, free = {0xffffc00037b8a000, 0xffffc00037b8b000...}}

CPU 2:

{static max = 512, nr = 92, free = {0xffffc0003f75b000, 0xffffc0003f75c000...}}

CPU 3:

{static max = 512, nr = 251, free = {0xffffc0003f613000, 0xffffc0003f614000...}}

Note that CPU 0 have given away one free page from its page buffer. Let's free the page

(gdb) p memory::free_page((void*)(0xffffc000247c6000))

$3 = void

(gdb) osv percpu memory::page_pool::percpu_l1

CPU 0:

{static max = 512, nr = 248, free = {0xffffc00023e80000, 0xffffc00023e81000...}}

CPU 1:

{static max = 512, nr = 42, free = {0xffffc00037b8a000, 0xffffc00037b8b000...}}

CPU 2:

{static max = 512, nr = 92, free = {0xffffc0003f75b000, 0xffffc0003f75c000...}}

CPU 3:

{static max = 512, nr = 251, free = {0xffffc0003f613000, 0xffffc0003f614000...}}

Indeed, the page is back to CPU 0's page buffer.

What happens when the page buffer is empty? In this case the CPU would refill it with at least 1 megabyte of pages in refill_page_buffer. Let's see that in action. We'll write a short python script that would drain all the free pages:

(gdb) pi

>>> for i in range(248):

... gdb.parse_and_eval('memory::alloc_page()')

...

<gdb.Value object at 0x7f0f40034a30>

...

>>>

Indeed, the number of free pages in CPU 0's buffer is zero:

(gdb) osv percpu memory::page_pool::percpu_l1

CPU 0:

{static max = 512, nr = 0, free = {0xffffc00023e80000, 0xffffc00023e81000...}}

CPU 1:

{static max = 512, nr = 42, free = {0xffffc00037b8a000, 0xffffc00037b8b000...}}

CPU 2:

{static max = 512, nr = 92, free = {0xffffc0003f75b000, 0xffffc0003f75c000...}}

CPU 3:

{static max = 512, nr = 251, free = {0xffffc0003f613000, 0xffffc0003f614000...}}

Now let's allocate another page

(gdb) p memory::alloc_page()

$3 = (void *) 0xffffc00023d44000

(gdb) osv percpu memory::page_pool::percpu_l1

CPU 0:

{static max = 512, nr = 255, free = {0xffffc00023c45000, 0xffffc00023c46000...}}

CPU 1:

{static max = 512, nr = 42, free = {0xffffc00037b8a000, 0xffffc00037b8b000...}}

CPU 2:

{static max = 512, nr = 92, free = {0xffffc0003f75b000, 0xffffc0003f75c000...}}

CPU 3:

{static max = 512, nr = 251, free = {0xffffc0003f613000, 0xffffc0003f614000...}}

Indeed, another megabyte of free pages is retrieved from the global free pages list.

What happens when the page buffer is full, and the CPU tries to free a page? In unfill_page_buffer, half of the pages in the page buffer are returned to free_page_ranges.

Here you go, no synchronization cost for most page allocations and deallocations, yet, a a simple design.