bun is a new:

- JavaScript runtime with Web APIs like

fetch,WebSocket, and several more built-in. bun embeds JavaScriptCore, which tends to be faster and more memory efficient than more popular engines like V8 (though harder to embed) - JavaScript/TypeScript/JSX transpiler

- JavaScript & CSS bundler

- Task runner for package.json scripts

- npm-compatible package manager

All in one fast & easy-to-use tool. Instead of 1,000 node_modules for development, you only need bun.

bun is experimental software. Join bun’s Discord for help and have a look at things that don’t work yet.

Today, bun's primary focus is bun.js: bun's JavaScript runtime.

Native: (macOS x64 & Silicon, Linux x64, Windows Subsystem for Linux)

curl -fsSL https://bun.sh/install | bashDocker: (Linux x64)

docker pull jarredsumner/bun:edge

docker run --rm --init --ulimit memlock=-1:-1 jarredsumner/bun:edgeIf using Linux, kernel version 5.6 or higher is strongly recommended, but the minimum is 5.1.

- Install

- Using bun.js - a new JavaScript runtime environment

- Using bun as a package manager

- Using bun as a task runner

- Creating a Discord bot with Bun

- Using bun with Next.js

- Using bun with single page apps

- Using bun with TypeScript

- Not implemented yet

- Configuration

- Troubleshooting

- Reference

Bun.serve- fast HTTP serverBun.write– optimizing I/O- bun:sqlite (SQLite3 module)

bun:ffi(Foreign Functions Interface)- Node-API (napi)

Bun.Transpiler- Environment variables

- Credits

- License

- Developing bun

- vscode-zig

bun.js focuses on performance, developer experience and compatibility with the JavaScript ecosystem.

// http.ts

export default {

port: 3000,

fetch(request: Request) {

return new Response("Hello World");

},

};

// bun ./http.ts| Requests per second | OS | CPU | bun version |

|---|---|---|---|

| 260,000 | macOS | Apple Silicon M1 Max | 0.0.76 |

| 160,000 | Linux | AMD Ryzen 5 3600 6-Core 2.2ghz | 0.0.76 |

Measured with http_load_test

by running:./http_load_test 20 127.0.0.1 3000bun.js prefers Web API compatibility instead of designing new APIs when possible. bun.js also implements some Node.js APIs.

- TypeScript & JSX support is builtin, powered by Bun's JavaScript transpiler

- ESM & CommonJS modules are supported (internally, bun.js uses ESM)

- Many npm packages "just work" with bun.js (when they use few/no node APIs)

- tsconfig.json

"paths"is natively supported, along with"exports"in package.json fs,path, andprocessfrom Node are partially implemented- Web APIs like

fetch,Response,URLand more are builtin HTMLRewritermakes it easy to transform HTML in bun.js- Starts 4x faster than Node (try it yourself)

.envfiles automatically load intoprocess.envandBun.env- top level await

The runtime uses JavaScriptCore, the JavaScript engine powering WebKit and Safari. Some web APIs like Headers and URL directly use Safari's implementation.

cat clone that runs 2x faster than GNU cat for large files on Linux

// cat.js

import { resolve } from "path";

import { write, stdout, file, argv } from "bun";

const path = resolve(argv.at(-1));

await write(

// stdout is a Blob

stdout,

// file(path) returns a Blob - https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/Blob

file(path)

);

// bun ./cat.js ./path-to-fileServer-side render React:

// requires Bun v0.1.0 or later

// react-ssr.tsx

import { renderToReadableStream } from "react-dom/server";

const dt = new Intl.DateTimeFormat();

export default {

port: 3000,

async fetch(request: Request) {

return new Response(

await renderToReadableStream(

<html>

<head>

<title>Hello World</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Hello from React!</h1>

<p>The date is {dt.format(new Date())}</p>

</body>

</html>

)

);

},

};

// bun react-ssr.tsxThere are some more examples in the examples folder.

PRs adding more examples are very welcome!

The best docs right now are the TypeScript types in the bun-types npm package. A docs site is coming soon.

To get autocomplete for bun.js types in your editor,

- Install the

bun-typesnpm package:

# yarn/npm/pnpm work too, "bun-types" is an ordinary npm package

bun add bun-types- Add this to your

tsconfig.jsonorjsconfig.json:

{

"compilerOptions": {

"lib": ["ESNext"],

"module": "esnext",

"target": "esnext",

// "bun-types" is the important part

"types": ["bun-types"]

}

}You can also view the types here.

bun.js has fast paths for common use cases that make Web APIs live up to the performance demands of servers and CLIs.

Bun.file(path) returns a Blob that represents a lazily-loaded file.

When you pass a file blob to Bun.write, Bun automatically uses a faster system call:

const blob = Bun.file("input.txt");

await Bun.write("output.txt", blob);On Linux, this uses the copy_file_range syscall and on macOS, this becomes clonefile (or fcopyfile).

Bun.write also supports Response objects. It automatically converts to a Blob.

// Eventually, this will stream the response to disk but today it buffers

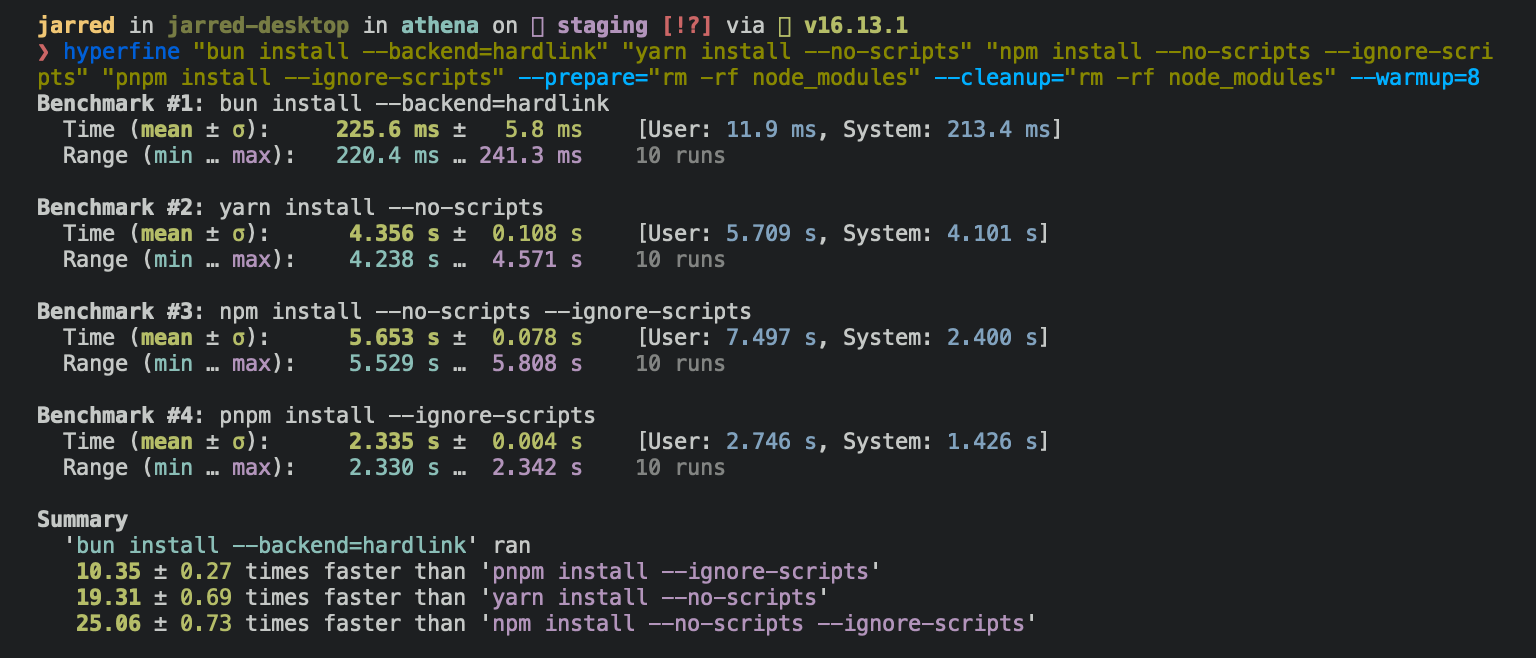

await Bun.write("index.html", await fetch("https://example.com"));On Linux, bun install tends to install packages 20x - 100x faster than npm install. On macOS, it’s more like 4x - 80x.

To install packages from package.json:

bun installTo add or remove packages from package.json:

bun remove react

bun add preactFor Linux users: bun install needs Linux Kernel 5.6 or higher to work well

The minimum Linux Kernel version is 5.1. If you're on Linux kernel 5.1 - 5.5, bun install should still work, but HTTP requests will be slow due to a lack of support for io_uring's connect() operation.

If you're using Ubuntu 20.04, here's how to install a newer kernel:

# If this returns a version >= 5.6, you don't need to do anything

uname -r

# Install the official Ubuntu hardware enablement kernel

sudo apt install --install-recommends linux-generic-hwe-20.04Instead of waiting 170ms for your npm client to start for each task, you wait 6ms for bun.

To use bun as a task runner, run bun run instead of npm run.

# Instead of "npm run clean"

bun run clean

# This also works

bun cleanAssuming a package.json with a "clean" command in "scripts":

{

"name": "myapp",

"scripts": {

"clean": "rm -rf dist out node_modules"

}

}Application commands are native ways to interact with apps in the Discord client. There are 3 types of commands accessible in different interfaces: the chat input, a message's context menu (top-right menu or right-clicking in a message), and a user's context menu (right-clicking on a user).

To get started you can use the interactions template:

bun create discord-interactions my-interactions-bot

cd my-interactions-botIf you don't have a Discord bot/application yet, you can create one here (https://discord.com/developers/applications/me).

Invite bot to your server by visiting https://discord.com/api/oauth2/authorize?client_id=<your_application_id>&scope=bot%20applications.commands

Afterwards you will need to get your bot's token, public key, and application id from the application page and put them into .env.example file

Then you can run the http server that will handle your interactions:

bun install

mv .env.example .env

bun run.js # listening on port 1337Discord does not accept an insecure HTTP server, so you will need to provide an SSL certificate or put the interactions server behind a secure reverse proxy. For development you can use ngrok/cloudflare tunnel to expose local ports as secure URL.

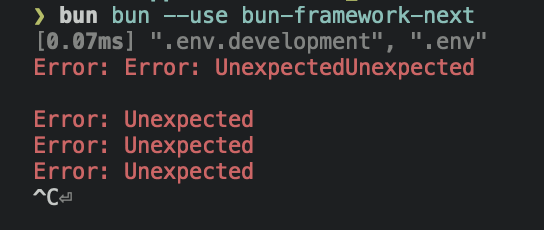

To create a new Next.js app with bun:

bun create next ./app

cd app

bun dev # start dev serverTo use an existing Next.js app with bun:

bun add bun-framework-next

echo "framework = 'next'" > bunfig.toml

bun bun # bundle dependencies

bun dev # start dev serverMany of Next.js’ features are supported, but not all.

Here’s what doesn’t work yet:

getStaticPaths- same-origin

fetchinside ofgetStaticPropsorgetServerSideProps - locales, zones,

assetPrefix(workaround: change--origin \"http://localhost:3000/assetPrefixInhere\") next/imageis polyfilled to a regular<img src>tag.proxyand anything else innext.config.js- API routes, middleware (middleware is easier to support though! similar SSR API)

- styled-jsx (technically not Next.js but often used with it)

- React Server Components

When using Next.js, bun automatically reads configuration from .env.local, .env.development and .env (in that order). process.env.NEXT_PUBLIC_ and process.env.NEXT_ automatically are replaced via --define.

Currently, any time you import new dependencies from node_modules, you will need to re-run bun bun --use next. This will eventually be automatic.

In your project folder root (where package.json is):

bun bun ./entry-point-1.js ./entry-point-2.jsx

bunBy default, bun will look for any HTML files in the public directory and serve that. For browsers navigating to the page, the .html file extension is optional in the URL, and index.html will automatically rewrite for the directory.

Here are examples of routing from public/ and how they’re matched:

| Dev Server URL | File Path |

|---|---|

| /dir | public/dir/index.html |

| / | public/index.html |

| /index | public/index.html |

| /hi | public/hi.html |

| /file | public/file.html |

| /font/Inter.woff2 | public/font/Inter.woff2 |

| /hello | public/index.html |

If public/index.html exists, it becomes the default page instead of a 404 page, unless that pathname has a file extension.

To create a new React app:

bun create react ./app

cd app

bun dev # start dev serverTo use an existing React app:

# To enable React Fast Refresh, ensure "react-refresh" is installed

npm install -D react-refresh

# Generate a bundle for your entry point(s)

bun bun ./src/index.js # jsx, tsx, ts also work. can be multiple files

# Start the dev server

bun devFrom there, bun relies on the filesystem for mapping dev server paths to source files. All URL paths are relative to the project root (where package.json is located).

Here are examples of routing source code file paths:

| Dev Server URL | File Path (relative to cwd) |

|---|---|

| /src/components/Button.tsx | src/components/Button.tsx |

| /src/index.tsx | src/index.tsx |

| /pages/index.js | pages/index.js |

You do not need to include file extensions in import paths. CommonJS-style import paths without the file extension work.

You can override the public directory by passing --public-dir="path-to-folder".

If no directory is specified and ./public/ doesn’t exist, bun will try ./static/. If ./static/ does not exist, but won’t serve from a public directory. If you pass --public-dir=./ bun will serve from the current directory, but it will check the current directory last instead of first.

TypeScript just works. There’s nothing to configure and nothing extra to install. If you import a .ts or .tsx file, bun will transpile it into JavaScript. bun also transpiles node_modules containing .ts or .tsx files. This is powered by bun’s TypeScript transpiler, so it’s fast.

bun also reads tsconfig.json, including baseUrl and paths.

To get TypeScript working with the global API, add bun-types to your project:

bun add -d bun-typesAnd to the types field in your tsconfig.json:

{

"compilerOptions": {

"types": ["bun-types"]

}

}bun is a project with an incredibly large scope and is still in its early days.

You can see Bun's Roadmap, but here are some additional things that are planned:

| Feature | In |

|---|---|

| Web Streams with Fetch API | bun.js |

| Web Streams with HTMLRewriter | bun.js |

| WebSocket Server | bun.js |

| Package hoisting that matches npm behavior | bun install |

| Source Maps (unbundled is supported) | JS Bundler |

| Source Maps | CSS |

| JavaScript Minifier | JS Transpiler |

| CSS Minifier | CSS |

| CSS Parser (it only bundles) | CSS |

| Tree-shaking | JavaScript |

| Tree-shaking | CSS |

extends in tsconfig.json |

TS Transpiler |

| TypeScript Decorators | TS Transpiler |

@jsxPragma comments |

JS Transpiler |

Sharing .bun files |

bun |

| Dates & timestamps | TOML parser |

| Hash components for Fast Refresh | JSX Transpiler |

TS Transpiler == TypeScript Transpiler

Package manager == `bun install`

bun.js == bun’s JavaScriptCore integration that executes JavaScript. Similar to how Node.js & Deno embed V8.

Today, bun is mostly focused on bun.js: the JavaScript runtime.

While you could use bun's bundler & transpiler separately to build for browsers or node, bun doesn't have a minifier or support tree-shaking yet. For production browser builds, you probably should use a tool like esbuild or swc.

Longer-term, bun intends to replace Node.js, Webpack, Babel, yarn, and PostCSS (in production).

- Bun's CLI flags will change to better support bun as a JavaScript runtime. They were chosen when bun was just a frontend development tool.

- Bun's bundling format will change to accommodate production browser bundles and on-demand production bundling

bunfig.toml is bun's configuration file.

It lets you load configuration from a file instead of passing flags to the CLI each time. The config file is loaded before CLI arguments are parsed, which means CLI arguments can override them.

Here is an example:

# Set a default framework to use

# By default, bun will look for an npm package like `bun-framework-${framework}`, followed by `${framework}`

framework = "next"

logLevel = "debug"

# publicDir = "public"

# external = ["jquery"]

[macros]

# Remap any import like this:

# import {graphql} from 'react-relay';

# To:

# import {graphql} from 'macro:bun-macro-relay';

react-relay = { "graphql" = "bun-macro-relay" }

[bundle]

saveTo = "node_modules.bun"

# Don't need this if `framework` is set, but showing it here as an example anyway

entryPoints = ["./app/index.ts"]

[bundle.packages]

# If you're bundling packages that do not actually live in a `node_modules` folder or do not have the full package name in the file path, you can pass this to bundle them anyway

"@bigapp/design-system" = true

[dev]

# Change the default port from 3000 to 5000

# Also inherited by Bun.serve

port = 5000

[define]

# Replace any usage of "process.env.bagel" with the string `lox`.

# The values are parsed as JSON, except single-quoted strings are supported and `'undefined'` becomes `undefined` in JS.

# This will probably change in a future release to be just regular TOML instead. It is a holdover from the CLI argument parsing.

"process.env.bagel" = "'lox'"

[loaders]

# When loading a .bagel file, run the JS parser

".bagel" = "js"

[debug]

# When navigating to a blob: or src: link, open the file in your editor

# If not, it tries $EDITOR or $VISUAL

# If that still fails, it will try Visual Studio Code, then Sublime Text, then a few others

# This is used by Bun.openInEditor()

editor = "code"

# List of editors:

# - "subl", "sublime"

# - "vscode", "code"

# - "textmate", "mate"

# - "idea"

# - "webstorm"

# - "nvim", "neovim"

# - "vim","vi"

# - "emacs"

# - "atom"

# If you pass it a file path, it will open with the file path instead

# It will recognize non-GUI editors, but I don't think it will work yetTODO: list each property name

A loader determines how to map imports & file extensions to transforms and output.

Currently, bun implements the following loaders:

| Input | Loader | Output |

|---|---|---|

| .js | JSX + JavaScript | .js |

| .jsx | JSX + JavaScript | .js |

| .ts | TypeScript + JavaScript | .js |

| .tsx | TypeScript + JSX + JavaScript | .js |

| .mjs | JavaScript | .js |

| .cjs | JavaScript | .js |

| .mts | TypeScript | .js |

| .cts | TypeScript | .js |

| .toml | TOML | .js |

| .css | CSS | .css |

| .env | Env | N/A |

| .* | file | string |

Everything else is treated as file. file replaces the import with a URL (or a path).

You can configure which loaders map to which extensions by passing --loaders to bun. For example:

bun --loader=.js:jsThis will disable JSX transforms for .js files.

When importing CSS in JavaScript-like loaders, CSS is treated special.

By default, bun will transform a statement like this:

import "../styles/global.css";globalThis.document?.dispatchEvent(

new CustomEvent("onimportcss", {

detail: "http://localhost:3000/styles/globals.css",

})

);An event handler for turning that into a <link> is automatically registered when HMR is enabled. That event handler can be turned off either in a framework’s package.json or by setting globalThis["Bun_disableCSSImports"] = true; in client-side code. Additionally, you can get a list of every .css file imported this way via globalThis["__BUN"].allImportedStyles.

//@import url("http://localhost:3000/styles/globals.css");Additionally, bun exposes an API for SSR/SSG that returns a flat list of URLs to css files imported. That function is Bun.getImportedStyles().

// This specifically is for "framework" in package.json when loaded via `bun dev`

// This API needs to be changed somewhat to work more generally with Bun.js

// Initially, you could only use bun.js through `bun dev`

// and this API was created at that time

addEventListener("fetch", async (event: FetchEvent) => {

var route = Bun.match(event);

const App = await import("pages/_app");

// This returns all .css files that were imported in the line above.

// It’s recursive, so any file that imports a CSS file will be included.

const appStylesheets = bun.getImportedStyles();

// ...rest of code

});This is useful for preventing flash of unstyled content.

bun bundles .css files imported via @import into a single file. It doesn’t autoprefix or minify CSS today. Multiple .css files imported in one JavaScript file will not be bundled into one file. You’ll have to import those from a .css file.

This input:

@import url("./hi.css");

@import url("./hello.css");

@import url("./yo.css");Becomes:

/* hi.css */

/* ...contents of hi.css */

/* hello.css */

/* ...contents of hello.css */

/* yo.css */

/* ...contents of yo.css */To support hot CSS reloading, bun inserts @supports annotations into CSS that tag which files a stylesheet is composed of. Browsers ignore this, so it doesn’t impact styles.

By default, bun’s runtime code automatically listens to onimportcss and will insert the event.detail into a <link rel="stylesheet" href={${event.detail}}> if there is no existing link tag with that stylesheet. That’s how bun’s equivalent of style-loader works.

Warning This will soon have breaking changes. It was designed when Bun was mostly a dev server and not a JavaScript runtime.

Frameworks preconfigure bun to enable developers to use bun with their existing tooling.

Frameworks are configured via the framework object in the package.json of the framework (not in the application’s package.json):

Here is an example:

{

"name": "bun-framework-next",

"version": "0.0.0-18",

"description": "",

"framework": {

"displayName": "Next.js",

"static": "public",

"assetPrefix": "_next/",

"router": {

"dir": ["pages", "src/pages"],

"extensions": [".js", ".ts", ".tsx", ".jsx"]

},

"css": "onimportcss",

"development": {

"client": "client.development.tsx",

"fallback": "fallback.development.tsx",

"server": "server.development.tsx",

"css": "onimportcss",

"define": {

"client": {

".env": "NEXT_PUBLIC_",

"defaults": {

"process.env.__NEXT_TRAILING_SLASH": "false",

"process.env.NODE_ENV": "\"development\"",

"process.env.__NEXT_ROUTER_BASEPATH": "''",

"process.env.__NEXT_SCROLL_RESTORATION": "false",

"process.env.__NEXT_I18N_SUPPORT": "false",

"process.env.__NEXT_HAS_REWRITES": "false",

"process.env.__NEXT_ANALYTICS_ID": "null",

"process.env.__NEXT_OPTIMIZE_CSS": "false",

"process.env.__NEXT_CROSS_ORIGIN": "''",

"process.env.__NEXT_STRICT_MODE": "false",

"process.env.__NEXT_IMAGE_OPTS": "null"

}

},

"server": {

".env": "NEXT_",

"defaults": {

"process.env.__NEXT_TRAILING_SLASH": "false",

"process.env.__NEXT_OPTIMIZE_FONTS": "false",

"process.env.NODE_ENV": "\"development\"",

"process.env.__NEXT_OPTIMIZE_IMAGES": "false",

"process.env.__NEXT_OPTIMIZE_CSS": "false",

"process.env.__NEXT_ROUTER_BASEPATH": "''",

"process.env.__NEXT_SCROLL_RESTORATION": "false",

"process.env.__NEXT_I18N_SUPPORT": "false",

"process.env.__NEXT_HAS_REWRITES": "false",

"process.env.__NEXT_ANALYTICS_ID": "null",

"process.env.__NEXT_CROSS_ORIGIN": "''",

"process.env.__NEXT_STRICT_MODE": "false",

"process.env.__NEXT_IMAGE_OPTS": "null",

"global": "globalThis",

"window": "undefined"

}

}

}

}

}

}Here are type definitions:

type Framework = Environment & {

// This changes what’s printed in the console on load

displayName?: string;

// This allows a prefix to be added (and ignored) to requests.

// Useful for integrating an existing framework that expects internal routes to have a prefix

// e.g. "_next"

assetPrefix?: string;

development?: Environment;

production?: Environment;

// The directory used for serving unmodified assets like fonts and images

// Defaults to "public" if exists, else "static", else disabled.

static?: string;

// "onimportcss" disables the automatic "onimportcss" feature

// If the framework does routing, you may want to handle CSS manually

// "facade" removes CSS imports from JavaScript files,

// and replaces an imported object with a proxy that mimics CSS module support without doing any class renaming.

css?: "onimportcss" | "facade";

// bun’s filesystem router

router?: Router;

};

type Define = {

// By passing ".env", bun will automatically load .env.local, .env.development, and .env if exists in the project root

// (in addition to the processes’ environment variables)

// When "*", all environment variables will be automatically injected into the JavaScript loader

// When a string like "NEXT_PUBLIC_", only environment variables starting with that prefix will be injected

".env": string | "*";

// These environment variables will be injected into the JavaScript loader

// These are the equivalent of Webpack’s resolve.alias and esbuild’s --define.

// Values are parsed as JSON, so they must be valid JSON. The only exception is '' is a valid string, to simplify writing stringified JSON in JSON.

// If not set, `process.env.NODE_ENV` will be transformed into "development".

defaults: Record<string, string>;

};

type Environment = {

// This is a wrapper for the client-side entry point for a route.

// This allows frameworks to run initialization code on pages.

client: string;

// This is a wrapper for the server-side entry point for a route.

// This allows frameworks to run initialization code on pages.

server: string;

// This runs when "server" code fails to load due to an exception.

fallback: string;

// This is how environment variables and .env is configured.

define?: Define;

};

// bun’s filesystem router

// Currently, bun supports pages by either an absolute match or a parameter match.

// pages/index.tsx will be executed on navigation to "/" and "/index"

// pages/posts/[id].tsx will be executed on navigation to "/posts/123"

// Routes & parameters are automatically passed to `fallback` and `server`.

type Router = {

// This determines the folder to look for pages

dir: string[];

// These are the allowed file extensions for pages.

extensions?: string[];

};To use a framework, you pass bun bun --use package-name.

Your framework’s package.json name should start with bun-framework-. This is so that people can type something like bun bun --use next and it will check bun-framework-next first. This is similar to how Babel plugins tend to start with babel-plugin-.

For developing frameworks, you can also do bun bun --use ./relative-path-to-framework.

If you’re interested in adding a framework integration, please reach out. There’s a lot here and it’s not entirely documented yet.

Bun currently only works on CPUs supporting the AVX2 instruction set. To run on older CPUs this can be emulated using Intel SDE, however bun won't be as fast as it would be when running on CPUs with AVX2 support. If you get this error while bun is initializing, You probably need to wrap the bun executable with intel-sde

- Install intel-sde

- Arch Linux:

yay -S intel-sde- Other Distros:

# wget https://downloadmirror.intel.com/732268/sde-external-9.7.0-2022-05-09-lin.tar.xz -O /tmp/intel-sde.tar.xz

# cd /tmp

# tar -xf intel-sde.tar.xz

# cd sde-external*

# mkdir /usr/local/bin -p

# cp sde64 /usr/local/bin/sde

# cp -r intel64 /usr/local/bin/

# cp -r misc /usr/local/bin/

- Add alias to bashrc

$ echo "alias bun='sde -chip-check-disable -- bun'" >> ~/.bashrc

You can replace .bashrc with .zshrc if you use zsh instead of bash

If you see a message like this

[1] 28447 killed bun create next ./test

It most likely means you’re running bun’s x64 version on Apple Silicon. This happens if bun is running via Rosetta. Rosetta is unable to emulate AVX2 instructions, which bun indirectly uses.

The fix is to ensure you installed a version of bun built for Apple Silicon.

If you see an error like this:

It usually means the max number of open file descriptors is being explicitly set to a low number. By default, bun requests the max number of file descriptors available (which on macOS, is something like 32,000). But, if you previously ran into ulimit issues with e.g. Chokidar, someone on The Internet may have advised you to run ulimit -n 8096.

That advice unfortunately lowers the hard limit to 8096. This can be a problem in large repositories or projects with lots of dependencies. Chokidar (and other watchers) don’t seem to call setrlimit, which means they’re reliant on the (much lower) soft limit.

To fix this issue:

- Remove any scripts that call

ulimit -nand restart your shell. - Try again, and if the error still occurs, try setting

ulimit -nto an absurdly high number, such asulimit -n 2147483646 - Try again, and if that still doesn’t fix it, open an issue

Unzip is required to install bun on Linux. You can use one of the following commands to install unzip:

sudo apt install unzipsudo dnf install unzipsudo pacman -S unzipsudo zypper install unzipPlease run bun install --verbose 2> logs.txt and send them to me in bun's discord. If you're on Linux, it would also be helpful if you run sudo perf trace bun install --silent and attach the logs.

bun install is a fast package manager & npm client.

bun install can be configured via bunfig.toml, environment variables, and CLI flags.

bunfig.toml is searched for in the following paths on bun install, bun remove, and bun add:

$XDG_CONFIG_HOME/.bunfig.tomlor$HOME/.bunfig.toml./bunfig.toml

If both are found, the results are merged together.

Configuring with bunfig.toml is optional. bun tries to be zero configuration in general, but that's not always possible.

# Using scoped packages with bun install

[install.scopes]

# Scope name The value can be a URL string or an object

"@mybigcompany" = { token = "123456", url = "https://registry.mybigcompany.com" }

# URL is optional and fallsback to the default registry

# The "@" in the scope is optional

mybigcompany2 = { token = "123456" }

# Environment variables can be referenced as a string that starts with $ and it will be replaced

mybigcompany3 = { token = "$npm_config_token" }

# Setting username and password turns it into a Basic Auth header by taking base64("username:password")

mybigcompany4 = { username = "myusername", password = "$npm_config_password", url = "https://registry.yarnpkg.com/" }

# You can set username and password in the registry URL. This is the same as above.

mybigcompany5 = "https://username:password@registry.yarnpkg.com/"

# You can set a token for a registry URL:

mybigcompany6 = "https://:$NPM_CONFIG_TOKEN@registry.yarnpkg.com/"

[install]

# Default registry

# can be a URL string or an object

registry = "https://registry.yarnpkg.com/"

# as an object

#registry = { url = "https://registry.yarnpkg.com/", token = "123456" }

# Install for production? This is the equivalent to the "--production" CLI argument

production = false

# Don't actually install

dryRun = true

# Install optionalDependencies (default: true)

optional = true

# Install local devDependencies (default: true)

dev = true

# Install peerDependencies (default: false)

peer = false

# When using `bun install -g`, install packages here

globalDir = "~/.bun/install/global"

# When using `bun install -g`, link package bins here

globalBinDir = "~/.bun/bin"

# cache-related configuration

[install.cache]

# The directory to use for the cache

dir = "~/.bun/install/cache"

# Don't load from the global cache.

# Note: bun may still write to node_modules/.cache

disable = false

# Always resolve the latest versions from the registry

disableManifest = false

# Lockfile-related configuration

[install.lockfile]

# Print a yarn v1 lockfile

# Note: it does not load the lockfile, it just converts bun.lockb into a yarn.lock

print = "yarn"

# Path to read bun.lockb from

path = "bun.lockb"

# Path to save bun.lockb to

savePath = "bun.lockb"

# Save the lockfile to disk

save = true

If it's easier to read as TypeScript types:

export interface Root {

install: Install;

}

export interface Install {

scopes: Scopes;

registry: Registry;

production: boolean;

dryRun: boolean;

optional: boolean;

dev: boolean;

peer: boolean;

globalDir: string;

globalBinDir: string;

cache: Cache;

lockfile: Lockfile;

logLevel: "debug" | "error" | "warn";

}

type Registry =

| string

| {

url?: string;

token?: string;

username?: string;

password?: string;

};

type Scopes = Record<string, Registry>;

export interface Cache {

dir: string;

disable: boolean;

disableManifest: boolean;

}

export interface Lockfile {

print?: "yarn";

path: string;

savePath: string;

save: boolean;

}Environment variables have a higher priority than bunfig.toml.

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| BUN_CONFIG_REGISTRY | Set an npm registry (default: https://registry.npmjs.org) |

| BUN_CONFIG_TOKEN | Set an auth token (currently does nothing) |

| BUN_CONFIG_LOCKFILE_SAVE_PATH | File path to save the lockfile to (default: bun.lockb) |

| BUN_CONFIG_YARN_LOCKFILE | Save a Yarn v1-style yarn.lock |

| BUN_CONFIG_LINK_NATIVE_BINS | Point bin in package.json to a platform-specific dependency |

| BUN_CONFIG_SKIP_SAVE_LOCKFILE | Don’t save a lockfile |

| BUN_CONFIG_SKIP_LOAD_LOCKFILE | Don’t load a lockfile |

| BUN_CONFIG_SKIP_INSTALL_PACKAGES | Don’t install any packages |

bun always tries to use the fastest available installation method for the target platform. On macOS, that’s clonefile and on Linux, that’s hardlink. You can change which installation method is used with the --backend flag. When unavailable or on error, clonefile and hardlink fallsback to a platform-specific implementation of copying files.

bun stores installed packages from npm in ~/.bun/install/cache/${name}@${version}. Note that if the semver version has a build or a pre tag, it is replaced with a hash of that value instead. This is to reduce the chances of errors from long file paths but unfortunately complicates figuring out where a package was installed on disk.

When the node_modules folder exists, before installing, bun checks if the "name" and "version" in package/package.json in the expected node_modules folder matches the expected name and version. This is how it determines whether or not it should install. It uses a custom JSON parser which stops parsing as soon as it finds "name" and "version".

When a bun.lockb doesn’t exist or package.json has changed dependencies, tarballs are downloaded & extracted eagerly while resolving.

When a bun.lockb exists and package.json hasn’t changed, bun downloads missing dependencies lazily. If the package with a matching name & version already exists in the expected location within node_modules, bun won’t attempt to download the tarball.

bun stores normalized cpu and os values from npm in the lockfile, along with the resolved packages. It skips downloading, extracting, and installing packages disabled for the current target at runtime. This means the lockfile won’t change between platforms/architectures even if the packages ultimately installed do change.

Peer dependencies are handled similarly to yarn. bun install does not automatically install peer dependencies and will try to choose an existing dependency.

bun.lockb is bun’s binary lockfile format.

In a word: Performance. bun’s lockfile saves & loads incredibly quickly, and saves a lot more data than what is typically inside lockfiles.

For now, the easiest thing is to run bun install -y. That prints a Yarn v1-style yarn.lock file.

Packages, metadata for those packages, the hoisted install order, dependencies for each package, what packages those dependencies resolved to, an integrity hash (if available), what each package was resolved to and which version (or equivalent)

It uses linear arrays for all data. Packages are referenced by auto-incrementing integer ID or a hash of the package name. Strings longer than 8 characters are de-duplicated. Prior to saving on disk, the lockfile is garbage-collected & made deterministic by walking the package tree and cloning the packages in dependency order.

To delete the cache:

rm -rf ~/.bun/install/cachebun uses a binary format for caching NPM registry responses. This loads much faster than JSON and tends to be smaller on disk.

You will see these files in ~/.bun/install/cache/*.npm. The filename pattern is ${hash(packageName)}.npm. It’s a hash so that extra directories don’t need to be created for scoped packages.

bun’s usage of Cache-Control ignores Age. This improves performance but means bun may be about 5 minutes out of date to receive the latest package version metadata from npm.

bun run is a fast package.json script runner. Instead of waiting 170ms for your npm client to start every time, you wait 6ms for bun.

By default, bun run prints the script that will be invoked:

bun run clean

$ rm -rf node_modules/.cache distYou can disable that with --silent

bun run --silent cleanbun run ${script-name} runs the equivalent of npm run script-name. For example, bun run dev runs the dev script in package.json, which may sometimes spin up non-bun processes.

bun run ${javascript-file.js} will run it with bun, as long as the file doesn't have a node shebang.

To print a list of scripts, bun run without additional args:

# This command

bun run

# Prints this

hello-create-react-app scripts:

bun run start

react-scripts start

bun run build

react-scripts build

bun run test

react-scripts test

bun run eject

react-scripts eject

4 scriptsbun run automatically loads environment variables from .env into the shell/task. .env files are loaded with the same priority as the rest of bun, so that means:

.env.localis first- if (

$NODE_ENV==="production").env.productionelse.env.development .env

If something is unexpected there, you can run bun run env to get a list of environment variables.

The default shell it uses is bash, but if that’s not found, it tries sh and if still not found, it tries zsh. This is not configurable right now, but if you care file an issue.

bun run automatically adds any parent node_modules/.bin to $PATH and if no scripts match, it will load that binary instead. That means you can run executables from packages too.

# If you use Relay

bun run relay-compiler

# You can also do this, but:

# - It will only lookup packages in `node_modules/.bin` instead of `$PATH`

# - It will start bun’s dev server if the script name doesn’t exist (`bun` starts the dev server by default)

bun relay-compilerTo pass additional flags through to the task or executable, there are two ways:

# Explicit: include "--" and anything after will be added. This is the recommended way because it is more reliable.

bun run relay-compiler -- -–help

# Implicit: if you do not include "--", anything *after* the script name will be passed through

# bun flags are parsed first, which means e.g. `bun run relay-compiler --help` will print bun’s help instead of relay-compiler’s help.

bun run relay-compiler --schema foo.graphqlbun run supports lifecycle hooks like post${task} and pre{task}. If they exist, they will run matching the behavior of npm clients. If the pre${task} fails, the next task will not be run. There is currently no flag to skip these lifecycle tasks if they exist, if you want that file an issue.

bun create is a fast way to create a new project from a template.

At the time of writing, bun create react app runs ~11x faster on my local computer than yarn create react-app app. bun create currently does no caching (though your npm client does)

Create a new Next.js project:

bun create next ./appCreate a new React project:

bun create react ./appCreate from a GitHub repo:

bun create ahfarmer/calculator ./appTo see a list of examples, run:

bun createFormat:

bun create github-user/repo-name destination

bun create local-example-or-remote-example destination

bun create /absolute/path/to-template-folder destination

bun create https://github.com/github-user/repo-name destination

bun create github.com/github-user/repo-name destinationNote: you don’t need bun create to use bun. You don’t need any configuration at all. This command exists to make it a little easier.

If you have your own boilerplate you prefer using, copy it into $HOME/.bun-create/my-boilerplate-name.

Before checking bun’s examples folder, bun create checks for a local folder matching the input in:

$BUN_CREATE_DIR/$HOME/.bun-create/$(pwd)/.bun-create/

If a folder exists in any of those folders with the input, bun will use that instead of a remote template.

To create a local template, run:

mkdir -p $HOME/.bun-create/new-template-name

echo '{"name":"new-template-name"}' > $HOME/.bun-create/new-template-name/package.jsonThis lets you run:

bun create new-template-name ./appNow your new template should appear when you run:

bun createWarning: unlike with remote templates, bun will delete the entire destination folder if it already exists.

| Flag | Description |

|---|---|

| --npm | Use npm for tasks & install |

| --yarn | Use yarn for tasks & install |

| --pnpm | Use pnpm for tasks & install |

| --force | Overwrite existing files |

| --no-install | Skip installing node_modules & tasks |

| --no-git | Don’t initialize a git repository |

| --open | Start & open in-browser after finish |

| Environment Variables | Description |

|---|---|

| GITHUB_API_DOMAIN | If you’re using a GitHub enterprise or a proxy, you can change what the endpoint requests to GitHub go |

| GITHUB_API_TOKEN | This lets bun create work with private repositories or if you get rate-limited |

By default, bun create will cancel if there are existing files it would overwrite and it's a remote template. You can pass --force to disable this behavior.

Clone this repository and a new folder in examples/ with your new template. The package.json must have a name that starts with @bun-examples/. Do not worry about publishing it, that will happen automatically after the PR is merged.

Make sure to include a .gitignore that includes node_modules so that node_modules aren’t checked in to git when people download the template.

To test your new template, add it as a local template or pass the absolute path.

bun create /path/to/my/new/template destination-dirWarning: This will always delete everything in destination-dir.

The bun-create section of package.json is automatically removed from the package.json on disk. This lets you add create-only steps without waiting for an extra package to install.

There are currently two options:

postinstallpreinstall

They can be an array of strings or one string. An array of steps will be executed in order.

Here is an example:

{

"name": "@bun-examples/next",

"version": "0.0.31",

"main": "index.js",

"dependencies": {

"next": "11.1.2",

"react": "^17.0.2",

"react-dom": "^17.0.2",

"react-is": "^17.0.2"

},

"devDependencies": {

"@types/react": "^17.0.19",

"bun-framework-next": "^0.0.0-21",

"typescript": "^4.3.5"

},

"bun-create": {

"postinstall": ["bun bun --use next"]

}

}By default, all commands run inside the environment exposed by the auto-detected npm client. This incurs a significant performance penalty, something like 150ms spent waiting for the npm client to start on each invocation.

Any command that starts with "bun " will be run without npm, relying on the first bun binary in $PATH.

When you run bun create ${template} ${destination}, here’s what happens:

IF remote template

-

GET

registry.npmjs.org/@bun-examples/${template}/latestand parse it -

GET

registry.npmjs.org/@bun-examples/${template}/-/${template}-${latestVersion}.tgz -

Decompress & extract

${template}-${latestVersion}.tgzinto${destination}- If there are files that would overwrite, warn and exit unless

--forceis passed

- If there are files that would overwrite, warn and exit unless

IF github repo

-

Download the tarball from GitHub’s API

-

Decompress & extract into

${destination}- If there are files that would overwrite, warn and exit unless

--forceis passed

- If there are files that would overwrite, warn and exit unless

ELSE IF local template

-

Open local template folder

-

Delete destination directory recursively

-

Copy files recursively using the fastest system calls available (on macOS

fcopyfileand Linux,copy_file_range). Do not copy or traverse intonode_modulesfolder if exists (this alone makes it faster thancp) -

Parse the

package.json(again!), updatenameto be${basename(destination)}, remove thebun-createsection from thepackage.jsonand save the updatedpackage.jsonto disk.- IF Next.js is detected, add

bun-framework-nextto the list of dependencies - IF Create React App is detected, add the entry point in /src/index.{js,jsx,ts,tsx} to

public/index.html - IF Relay is detected, add

bun-macro-relayso that Relay works

- IF Next.js is detected, add

-

Auto-detect the npm client, preferring

pnpm,yarn(v1), and lastlynpm -

Run any tasks defined in

"bun-create": { "preinstall" }with the npm client -

Run

${npmClient} installunless--no-installis passed OR no dependencies are in package.json -

Run any tasks defined in

"bun-create": { "preinstall" }with the npm client -

Run

git init; git add -A .; git commit -am "Initial Commit";- Rename

gitignoreto.gitignore. NPM automatically removes.gitignorefiles from appearing in packages. - If there are dependencies, this runs in a separate thread concurrently while node_modules are being installed

- Using libgit2 if available was tested and performed 3x slower in microbenchmarks

- Rename

-

Done

misctools/publish-examples.js publishes all examples to npm.

Run bun bun ./path-to.js to generate a node_modules.bun file containing all imported dependencies (recursively).

- For browsers, loading entire apps without bundling dependencies is typically slow. With a fast bundler & transpiler, the bottleneck eventually becomes the web browser’s ability to run many network requests concurrently. There are many workarounds for this.

<link rel="modulepreload">, HTTP/3, etc but none are more effective than bundling. If you have reproducible evidence to the contrary, feel free to submit an issue. It would be better if bundling wasn’t necessary. - On the server, bundling reduces the number of filesystem lookups to load JavaScript. While filesystem lookups are faster than HTTP requests, there’s still overhead.

Note: This format may change soon

The .bun file contains:

- all the bundled source code

- all the bundled source code metadata

- project metadata & configuration

Here are some of the questions .bun files answer:

- when I import

react/index.js, where in the.bunis the code for that? (not resolving, just the code) - what modules of a package are used?

- what framework is used? (e.g. Next.js)

- where is the routes directory?

- how big is each imported dependency?

- what is the hash of the bundle’s contents? (for etags)

- what is the name & version of every npm package exported in this bundle?

- what modules from which packages are used in this project? ("project" is defined as all the entry points used to generate the .bun)

All in one file.

It’s a little like a build cache but designed for reuse across builds.

From a design perspective, the most important part of the .bun format is how code is organized. Each module is exported by a hash like this:

// preact/dist/preact.module.js

export var $eb6819b = $$m({

"preact/dist/preact.module.js": (module, exports) => {

var n, l, u, i, t, o, r, f, e = {}, c = [], s = /acit|ex(?:s|g|n|p|$)|rph|grid|ows|mnc|ntw|ine[ch]|zoo|^ord|itera/i;

// ... rest of codeThis makes bundled modules position-independent. In theory, one could import only the exact modules in-use without reparsing code and without generating a new bundle. One bundle can dynamically become many bundles comprising only the modules in use on the webpage. Thanks to the metadata with the byte offsets, a web server can send each module to browsers zero-copy using sendfile. bun itself is not quite this smart yet, but these optimizations would be useful in production and potentially very useful for React Server Components.

To see the schema inside, have a look at JavascriptBundleContainer. You can find JavaScript bindings to read the metadata in src/api/schema.js. This is not really an API yet. It’s missing the part where it gets the binary data from the bottom of the file. Someday, I want this to be usable by other tools too.

.bun files are marked as executable.

To print out the code, run ./node_modules.bun in your terminal or run bun ./path-to-node_modules.bun.

Here is a copy-pastable example:

./node_modules.bun > node_modules.jsThis works because every .bun file starts with this:

#!/usr/bin/env bunTo deploy to production with bun, you’ll want to get the code from the .bun file and stick that somewhere your web server can find it (or if you’re using Vercel or a Rails app, in a public folder).

Note that .bun is a binary file format, so just opening it in VSCode or vim might render strangely.

By default, bun bun only bundles external dependencies that are imported or required in either app code or another external dependency. An "external dependency" is defined as, "A JavaScript-like file that has /node_modules/ in the resolved file path and a corresponding package.json".

To force bun to bundle packages which are not located in a node_modules folder (i.e. the final, resolved path following all symlinks), add a bun section to the root project’s package.json with alwaysBundle set to an array of package names to always bundle. Here’s an example:

{

"name": "my-package-name-in-here",

"bun": {

"alwaysBundle": ["@mybigcompany/my-workspace-package"]

}

}Bundled dependencies are not eligible for Hot Module Reloading. The code is served to browsers & bun.js verbatim. But, in the future, it may be sectioned off into only parts of the bundle being used. That’s possible in the current version of the .bun file (so long as you know which files are necessary), but it’s not implemented yet. Longer-term, it will include all import and export of each module inside.

The $eb6819b hash used here:

export var $eb6819b = $$m({Is generated like this:

- Murmur3 32-bit hash of

package.name@package.version. This is the hash uniquely identifying the npm package. - Wyhash 64 of the

package.hash+package_path.package_pathmeans "relative to the root of the npm package, where is the module imported?". For example, if you importedreact/jsx-dev-runtime.js, thepackage_pathisjsx-dev-runtime.js.react-dom/cjs/react-dom.development.jswould becjs/react-dom.development.js - Truncate the hash generated above to a

u32

The implementation details of this module ID hash will vary between versions of bun. The important part is the metadata contains the module IDs, the package paths, and the package hashes so it shouldn’t really matter in practice if other tooling wants to make use of any of this.

To upgrade bun, run bun upgrade.

It automatically downloads the latest version of bun and overwrites the currently-running version.

This works by checking the latest version of bun in bun-releases-for-updater and unzipping it using the system-provided unzip library (so that Gatekeeper works on macOS)

If for any reason you run into issues, you can also use the curl install script:

curl https://bun.sh/install | bashIt will still work when bun is already installed.

bun is distributed as a single binary file, so you can also do this manually:

- Download the latest version of bun for your platform in bun-releases-for-updater (

darwin== macOS) - Unzip the folder

- Move the

bunbinary to~/.bun/bin(or anywhere)

This command installs completions for zsh and/or fish. It’s run automatically on every bun upgrade and on install. It reads from $SHELL to determine which shell to install for. It tries several common shell completion directories for your shell and OS.

If you want to copy the completions manually, run bun completions > path-to-file. If you know the completions directory to install them to, run bun completions /path/to/directory.

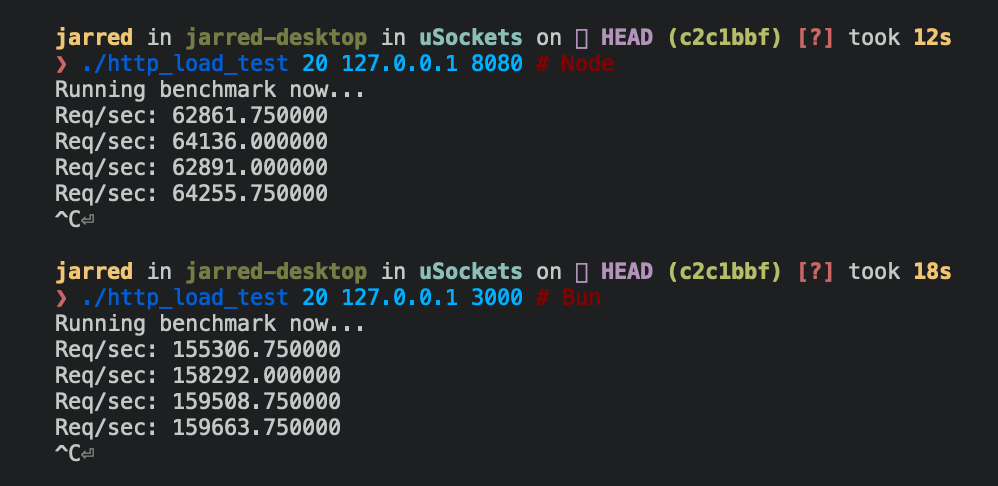

For a hello world HTTP server that writes "bun!", Bun.serve serves about 2.5x more requests per second than node.js on Linux:

| Requests per second | Runtime |

|---|---|

| ~64,000 | Node 16 |

| ~160,000 | Bun |

Bigger is better

Code

Bun:

Bun.serve({

fetch(req: Request) {

return new Response(`bun!`);

},

port: 3000,

});Node:

require("http")

.createServer((req, res) => res.end("bun!"))

.listen(8080);

Two ways to start an HTTP server with bun.js:

export defaultan object with afetchfunction

If the file used to start bun has a default export with a fetch function, it will start the HTTP server.

// hi.js

export default {

fetch(req) {

return new Response("HI!");

},

};

// bun ./hi.jsfetch receives a Request object and must return either a Response or a Promise<Response>. In a future version, it might have additional arguments for things like cookies.

Bun.servestarts the HTTP server explicitly

Bun.serve({

fetch(req) {

return new Response("HI!");

},

});For error handling, you get an error function.

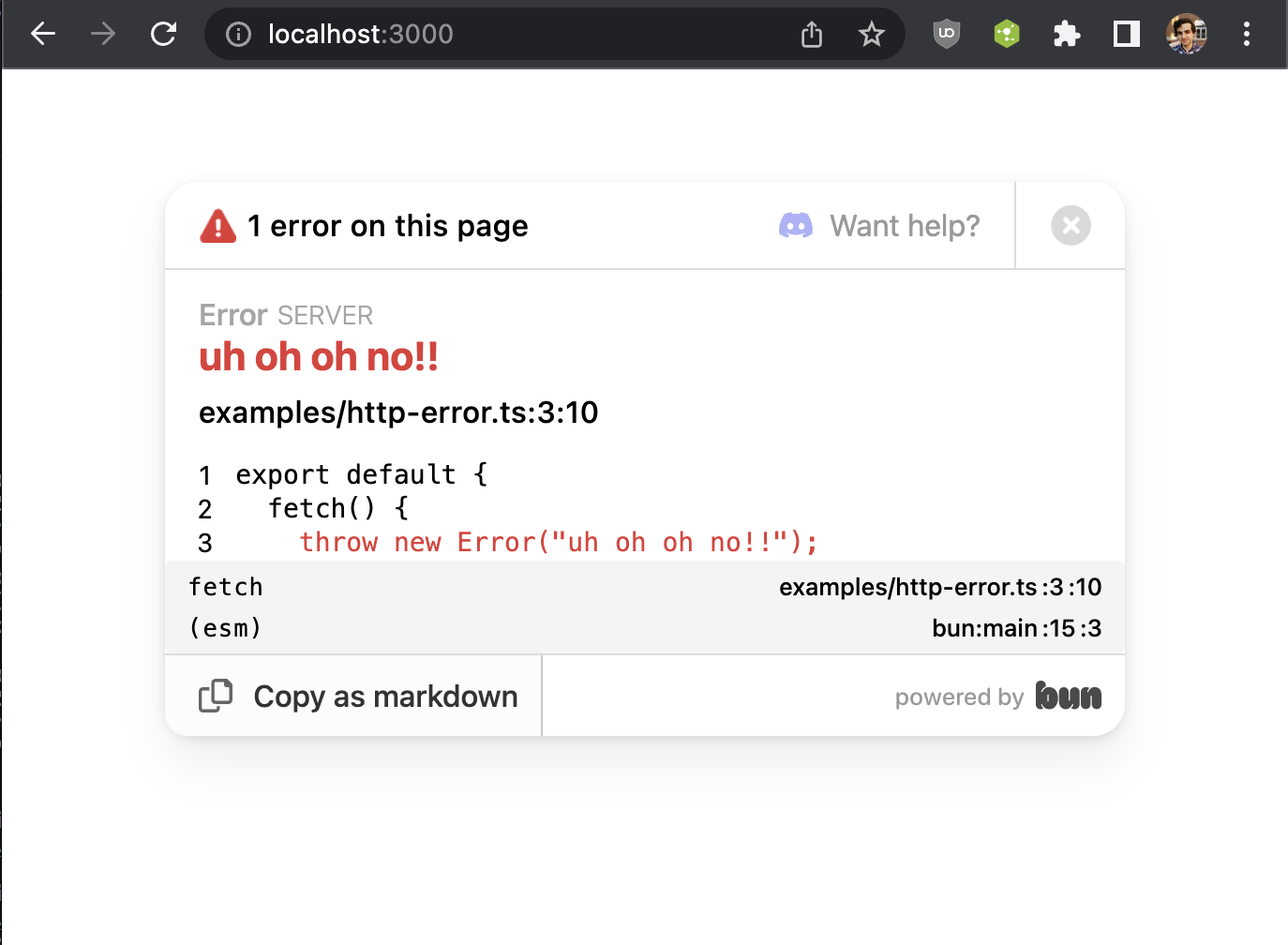

If development: true and error is not defined or doesn't return a Response, you will get an exception page with a stack trace:

It will hopefully make it easier to debug issues with bun until bun gets debugger support. This error page is based on what bun dev does.

If the error function returns a Response, it will be served instead

Bun.serve({

fetch(req) {

throw new Error("woops!");

},

error(error: Error) {

return new Response("Uh oh!!\n" + error.toString(), { status: 500 });

},

});If the error function itself throws and development is false, a generic 500 page will be shown

To stop the server, call server.stop():

const server = Bun.serve({

fetch() {

return new Response("HI!");

},

});

server.stop();The interface for Bun.serve is based on what Cloudflare Workers does.

Bun.write lets you write, copy or pipe files automatically using the fastest system calls compatible with the input and platform.

interface Bun {

write(

destination: string | number | FileBlob,

input: string | FileBlob | Blob | ArrayBufferView

): Promise<number>;

}| Output | Input | System Call | Platform |

|---|---|---|---|

| file | file | copy_file_range | Linux |

| file | pipe | sendfile | Linux |

| pipe | pipe | splice | Linux |

| terminal | file | sendfile | Linux |

| terminal | terminal | sendfile | Linux |

| socket | file or pipe | sendfile (if http, not https) | Linux |

| file (path, doesn't exist) | file (path) | clonefile | macOS |

| file | file | fcopyfile | macOS |

| file | Blob or string | write | macOS |

| file | Blob or string | write | Linux |

All this complexity is handled by a single function.

// Write "Hello World" to output.txt

await Bun.write("output.txt", "Hello World");// log a file to stdout

await Bun.write(Bun.stdout, Bun.file("input.txt"));// write the HTTP response body to disk

await Bun.write("index.html", await fetch("http://example.com"));

// this does the same thing

await Bun.write(Bun.file("index.html"), await fetch("http://example.com"));// copy input.txt to output.txt

await Bun.write("output.txt", Bun.file("input.txt"));bun:sqlite is a high-performance builtin SQLite3 module for bun.js.

- Simple, synchronous API (synchronous is faster)

- Transactions

- Binding named & positional parameters

- Prepared statements

- Automatic type conversions (

BLOBbecomesUint8Array) - toString() prints as SQL

Installation:

# there's nothing to install

# bun:sqlite is builtin to bun.jsExample:

import { Database } from "bun:sqlite";

const db = new Database("mydb.sqlite");

db.run(

"CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS foo (id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT, greeting TEXT)"

);

db.run("INSERT INTO foo (greeting) VALUES (?)", "Welcome to bun!");

db.run("INSERT INTO foo (greeting) VALUES (?)", "Hello World!");

// get the first row

db.query("SELECT * FROM foo").get();

// { id: 1, greeting: "Welcome to bun!" }

// get all rows

db.query("SELECT * FROM foo").all();

// [

// { id: 1, greeting: "Welcome to bun!" },

// { id: 2, greeting: "Hello World!" },

// ]

// get all rows matching a condition

db.query("SELECT * FROM foo WHERE greeting = ?").all("Welcome to bun!");

// [

// { id: 1, greeting: "Welcome to bun!" },

// ]

// get first row matching a named condition

db.query("SELECT * FROM foo WHERE greeting = $greeting").get({

$greeting: "Welcome to bun!",

});

// [

// { id: 1, greeting: "Welcome to bun!" },

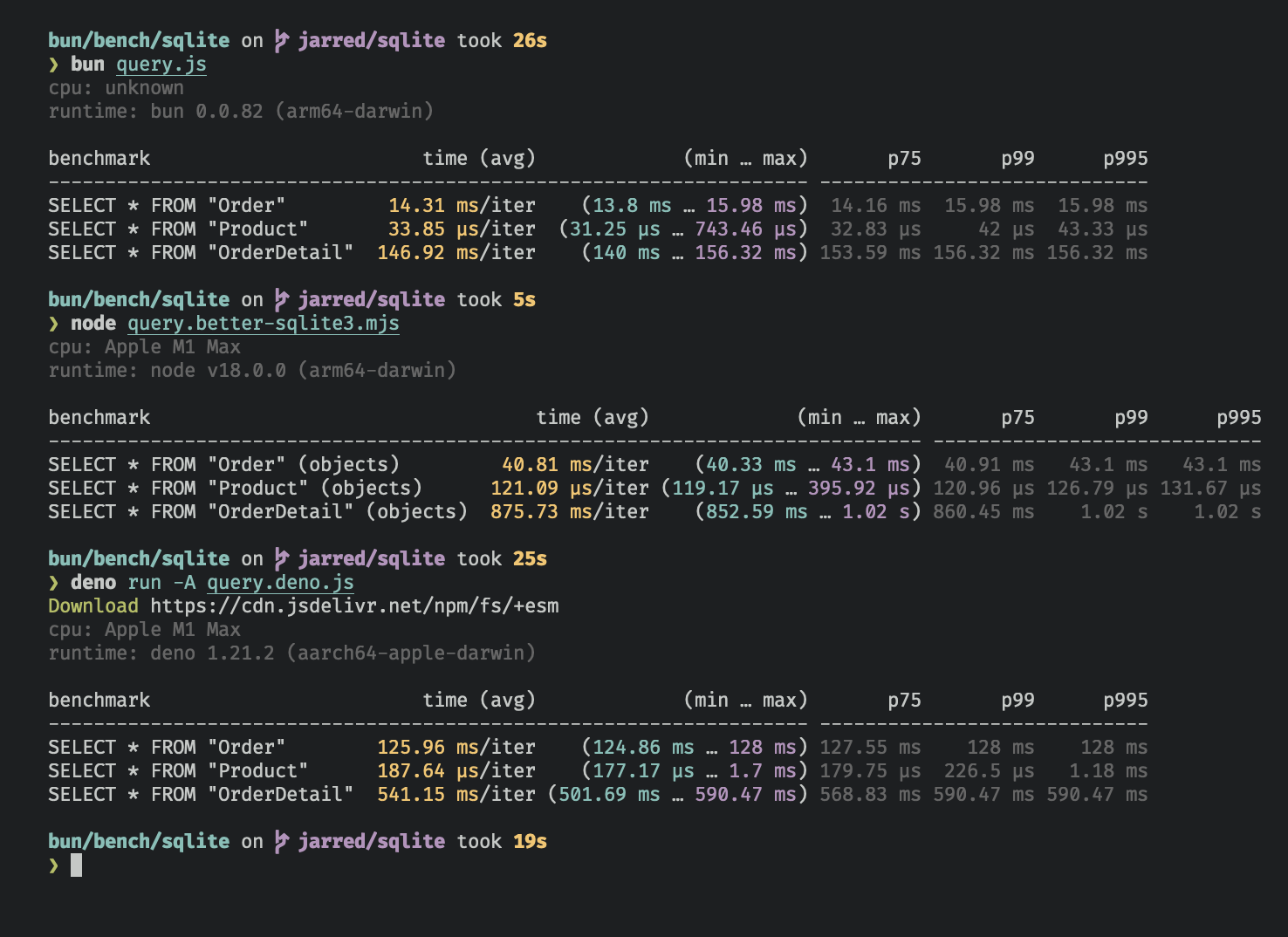

// ]Database: Northwind Traders.

This benchmark can be run from ./bench/sqlite.

Here are results from an M1 Pro (64GB) on macOS 12.3.1.

SELECT * FROM "Order"

| Library | Runtime | ms/iter |

|---|---|---|

| bun:sqlite3 | Bun 0.0.83 | 14.31 (1x) |

| better-sqlite3 | Node 18.0.0 | 40.81 (2.8x slower) |

| deno.land/x/sqlite | Deno 1.21.2 | 125.96 (8.9x slower) |

SELECT * FROM "Product"

| Library | Runtime | us/iter |

|---|---|---|

| bun:sqlite3 | Bun 0.0.83 | 33.85 (1x) |

| better-sqlite3 | Node 18.0.0 | 121.09 (3.5x slower) |

| deno.land/x/sqlite | Deno 1.21.2 | 187.64 (8.9x slower) |

SELECT * FROM "OrderDetail"

| Library | Runtime | ms/iter |

|---|---|---|

| bun:sqlite3 | Bun 0.0.83 | 146.92 (1x) |

| better-sqlite3 | Node 18.0.0 | 875.73 (5.9x slower) |

| deno.land/x/sqlite | Deno 1.21.2 | 541.15 (3.6x slower) |

In screenshot form (which has a different sorting order)

bun:sqlite's API is loosely based on better-sqlite3, though the implementation is different.

bun:sqlite has two classes:

class Databaseclass Statement

Calling new Database(filename) opens or creates the SQLite database.

constructor(

filename: string,

options?:

| number

| {

/**

* Open the database as read-only (no write operations, no create).

*

* Equivalent to {@link constants.SQLITE_OPEN_READONLY}

*/

readonly?: boolean;

/**

* Allow creating a new database

*

* Equivalent to {@link constants.SQLITE_OPEN_CREATE}

*/

create?: boolean;

/**

* Open the database as read-write

*

* Equivalent to {@link constants.SQLITE_OPEN_READWRITE}

*/

readwrite?: boolean;

}

);To open or create a SQLite3 database:

import { Database } from "bun:sqlite";

const db = new Database("mydb.sqlite");Open an in-memory database:

import { Database } from "bun:sqlite";

// all of these do the same thing

var db = new Database(":memory:");

var db = new Database();

var db = new Database("");Open read-write and throw if the database doesn't exist:

import { Database } from "bun:sqlite";

const db = new Database("mydb.sqlite", { readwrite: true });Open read-only and throw if the database doesn't exist:

import { Database } from "bun:sqlite";

const db = new Database("mydb.sqlite", { readonly: true });Open read-write, don't throw if new file:

import { Database } from "bun:sqlite";

const db = new Database("mydb.sqlite", { readonly: true, create: true });Open a database from a Uint8Array:

import { Database } from "bun:sqlite";

import { readFileSync } from "fs";

// unlike passing a filepath, this will not persist any changes to disk

// it will be read-write but not persistent

const db = new Database(readFileSync("mydb.sqlite"));Close a database:

var db = new Database();

db.close();Note: close() is called automatically when the database is garbage collected. It is safe to call multiple times but has no effect after the first.

query(sql) creates a Statement for the given SQL and caches it, but does not execute it.

class Database {

query(sql: string): Statement;

}query returns a Statement object.

It performs the same operation as Database.prototype.prepare, except:

querycaches the prepared statement in theDatabaseobjectquerydoesn't bind parameters

This intended to make it easier for bun:sqlite to be fast by default. Calling .prepare compiles a SQLite query, which can take some time, so it's better to cache those a little.

You can bind parameters on any call to a statement.

import { Database } from "bun:sqlite";

// generate some data

var db = new Database();

db.run(

"CREATE TABLE foo (id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT, greeting TEXT)"

);

db.run("INSERT INTO foo (greeting) VALUES ($greeting)", {

$greeting: "Welcome to bun",

});

// get the query

const stmt = db.query("SELECT * FROM foo WHERE greeting = ?");

// run the query

stmt.all("Welcome to bun!");

stmt.get("Welcome to bun!");

stmt.run("Welcome to bun!");prepare(sql) creates a Statement for the given SQL, but does not execute it.

Unlike query(), this does not cache the compiled query.

import { Database } from "bun:sqlite";

// generate some data

var db = new Database();

db.run(

"CREATE TABLE foo (id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT, greeting TEXT)"

);

// compile the prepared statement

const stmt = db.prepare("SELECT * FROM foo WHERE bar = ?");

// run the prepared statement

stmt.all("baz");Internally, this calls sqlite3_prepare_v3.

exec is for one-off executing a query which does not need to return anything.

run is an alias.

class Database {

// exec is an alias for run

exec(sql: string, ...params: ParamsType): void;

run(sql: string, ...params: ParamsType): void;

}This is useful for things like

Creating a table:

import { Database } from "bun:sqlite";

var db = new Database();

db.exec(

"CREATE TABLE foo (id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT, greeting TEXT)"

);Inserting one row:

import { Database } from "bun:sqlite";

var db = new Database();

db.exec(

"CREATE TABLE foo (id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT, greeting TEXT)"

);

// insert one row

db.exec("INSERT INTO foo (greeting) VALUES ($greeting)", {

$greeting: "Welcome to bun",

});For queries which aren't intended to be run multiple times, it should be faster to use exec() than prepare() or query() because it doesn't create a Statement object.

Internally, this function calls sqlite3_prepare, sqlite3_step, and sqlite3_finalize.

Creates a function that always runs inside a transaction. When the function is invoked, it will begin a new transaction. When the function returns, the transaction will be committed. If an exception is thrown, the transaction will be rolled back (and the exception will propagate as usual).

// setup

import { Database } from "bun:sqlite";

const db = Database.open(":memory:");

db.exec(

"CREATE TABLE cats (id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT, name TEXT UNIQUE, age INTEGER)"

);

const insert = db.prepare("INSERT INTO cats (name, age) VALUES ($name, $age)");

const insertMany = db.transaction((cats) => {

for (const cat of cats) insert.run(cat);

});

insertMany([

{ $name: "Joey", $age: 2 },

{ $name: "Sally", $age: 4 },

{ $name: "Junior", $age: 1 },

]);Transaction functions can be called from inside other transaction functions. When doing so, the inner transaction becomes a savepoint.

// setup

import { Database } from "bun:sqlite";

const db = Database.open(":memory:");

db.exec(

"CREATE TABLE expenses (id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT, note TEXT, dollars INTEGER);"

);

db.exec(

"CREATE TABLE cats (id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT, name TEXT UNIQUE, age INTEGER)"

);

const newExpense = db.prepare(

"INSERT INTO expenses (note, dollars) VALUES (?, ?)"

);

const insert = db.prepare("INSERT INTO cats (name, age) VALUES ($name, $age)");

const insertMany = db.transaction((cats) => {

for (const cat of cats) insert.run(cat);

});

const adopt = db.transaction((cats) => {

newExpense.run("adoption fees", 20);

insertMany(cats); // nested transaction

});

adopt([

{ $name: "Joey", $age: 2 },

{ $name: "Sally", $age: 4 },

{ $name: "Junior", $age: 1 },

]);Transactions also come with deferred, immediate, and exclusive versions.

insertMany(cats); // uses "BEGIN"

insertMany.deferred(cats); // uses "BEGIN DEFERRED"

insertMany.immediate(cats); // uses "BEGIN IMMEDIATE"

insertMany.exclusive(cats); // uses "BEGIN EXCLUSIVE"Any arguments passed to the transaction function will be forwarded to the wrapped function, and any values returned from the wrapped function will be returned from the transaction function. The wrapped function will also have access to the same binding as the transaction function.

bun:sqlite's transaction implementation is based on better-sqlite3 (along with this section of the docs), so thanks to Joshua Wise and better-sqlite3 contributors.

SQLite has a builtin way to serialize and deserialize databases to and from memory.

bun:sqlite fully supports it:

var db = new Database();

// write some data

db.run(

"CREATE TABLE foo (id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT, greeting TEXT)"

);

db.run("INSERT INTO foo VALUES (?)", "Welcome to bun!");

db.run("INSERT INTO foo VALUES (?)", "Hello World!");

const copy = db.serialize();

// => Uint8Array

const db2 = new Database(copy);

db2.query("SELECT * FROM foo").all();

// => [

// { id: 1, greeting: "Welcome to bun!" },

// { id: 2, greeting: "Hello World!" },

// ]db.serialize() returns a Uint8Array of the database.

Internally, it calls sqlite3_serialize.

bun:sqlite supports SQLite extensions.

To load a SQLite extension, call Database.prototype.loadExtension(name):

import { Database } from "bun:sqlite";

var db = new Database();

db.loadExtension("myext");If you're on macOS, you will need to first use a custom SQLite install (you can install with homebrew). By default, bun uses Apple's proprietary build of SQLite because it benchmarks about 50% faster. However, they disabled extension support, so you will need to have a custom build of SQLite to use extensions on macOS.

import { Database } from "bun:sqlite";

// on macOS, this must be run before any other calls to `Database`

// if called on linux, it will return true and do nothing

// on linux it will still check that a string was passed

Database.setCustomSQLite("/path/to/sqlite.dylib");

var db = new Database();

db.loadExtension("myext");To install sqlite with homebrew:

brew install sqliteStatement is a prepared statement. Use it to run queries that get results.

TLDR:

Statement.all(...optionalParamsToBind)returns all rows as an array of objectsStatement.values(...optionalParamsToBind)returns all rows as an array of arraysStatement.get(...optionalParamsToBind)returns the first row as an objectStatement.run(...optionalParamsToBind)runs the statement and returns nothingStatement.finalize()closes the statementStatement.toString()prints the expanded SQL, including bound parametersget Statement.columnNamesget the returned column namesget Statement.paramsCounthow many parameters are expected?

You can bind parameters on any call to a statement. Named parameters and positional parameters are supported. Bound parameters are remembered between calls and reset the next time you pass parameters to bind.

import { Database } from "bun:sqlite";

// setup

var db = new Database();

db.run(

"CREATE TABLE foo (id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT, greeting TEXT)"

);

db.run("INSERT INTO foo VALUES (?)", "Welcome to bun!");

db.run("INSERT INTO foo VALUES (?)", "Hello World!");

// Statement object

var statement = db.query("SELECT * FROM foo");

// returns all the rows

statement.all();

// returns the first row

statement.get();

// runs the query, without returning anything

statement.run();Calling all() on a Statement instance runs the query and returns the rows as an array of objects.

import { Database } from "bun:sqlite";

// setup

var db = new Database();

db.run(

"CREATE TABLE foo (id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT, greeting TEXT, count INTEGER)"

);

db.run("INSERT INTO foo (greeting, count) VALUES (?, ?)", "Welcome to bun!", 2);

db.run("INSERT INTO foo (greeting, count) VALUES (?, ?)", "Hello World!", 0);

db.run(

"INSERT INTO foo (greeting, count) VALUES (?, ?)",

"Welcome to bun!!!!",

2

);

// Statement object

var statement = db.query("SELECT * FROM foo WHERE count = ?");

// return all the query results, binding 2 to the count parameter

statement.all(2);

// => [

// { id: 1, greeting: "Welcome to bun!", count: 2 },

// { id: 3, greeting: "Welcome to bun!!!!", count: 2 },

// ]Internally, this calls sqlite3_reset and repeatedly calls sqlite3_step until it returns SQLITE_DONE.

Calling values() on a Statement instance runs the query and returns the rows as an array of arrays.

import { Database } from "bun:sqlite";

// setup

var db = new Database();

db.run(

"CREATE TABLE foo (id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT, greeting TEXT, count INTEGER)"

);

db.run("INSERT INTO foo (greeting, count) VALUES (?, ?)", "Welcome to bun!", 2);

db.run("INSERT INTO foo (greeting, count) VALUES (?, ?)", "Hello World!", 0);

db.run(

"INSERT INTO foo (greeting, count) VALUES (?, ?)",

"Welcome to bun!!!!",

2

);

// Statement object

var statement = db.query("SELECT * FROM foo WHERE count = ?");

// return all the query results as an array of arrays, binding 2 to "count"

statement.values(2);

// => [

// [ 1, "Welcome to bun!", 2 ],

// [ 3, "Welcome to bun!!!!", 2 ],

// ]

// Statement object, but with named parameters

var statement = db.query("SELECT * FROM foo WHERE count = $count");

// return all the query results as an array of arrays, binding 2 to "count"

statement.values({ $count: 2 });

// => [

// [ 1, "Welcome to bun!", 2 ],

// [ 3, "Welcome to bun!!!!", 2 ],

// ]Internally, this calls sqlite3_reset and repeatedly calls sqlite3_step until it returns SQLITE_DONE.

Calling get() on a Statement instance runs the query and returns the first result as an object.

import { Database } from "bun:sqlite";

// setup

var db = new Database();

db.run(

"CREATE TABLE foo (id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT, greeting TEXT, count INTEGER)"

);

db.run("INSERT INTO foo (greeting, count) VALUES (?, ?)", "Welcome to bun!", 2);

db.run("INSERT INTO foo (greeting, count) VALUES (?, ?)", "Hello World!", 0);

db.run(

"INSERT INTO foo (greeting, count) VALUES (?, ?)",

"Welcome to bun!!!!",

2

);

// Statement object

var statement = db.query("SELECT * FROM foo WHERE count = ?");

// return the first row as an object, binding 2 to the count parameter

statement.get(2);

// => { id: 1, greeting: "Welcome to bun!", count: 2 }

// Statement object, but with named parameters

var statement = db.query("SELECT * FROM foo WHERE count = $count");

// return the first row as an object, binding 2 to the count parameter

statement.get({ $count: 2 });

// => { id: 1, greeting: "Welcome to bun!", count: 2 }Internally, this calls sqlite3_reset and calls sqlite3_step once. Stepping through all the rows is not necessary when you only want the first row.

Calling run() on a Statement instance runs the query and returns nothing.

This is useful if you want to repeatedly run a query, but don't care about the results.

import { Database } from "bun:sqlite";

// setup

var db = new Database();

db.run(

"CREATE TABLE foo (id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT, greeting TEXT, count INTEGER)"

);

db.run("INSERT INTO foo (greeting, count) VALUES (?, ?)", "Welcome to bun!", 2);

db.run("INSERT INTO foo (greeting, count) VALUES (?, ?)", "Hello World!", 0);

db.run(

"INSERT INTO foo (greeting, count) VALUES (?, ?)",

"Welcome to bun!!!!",

2

);

// Statement object (TODO: use a better example query)

var statement = db.query("SELECT * FROM foo");

// run the query, returning nothing

statement.run();Internally, this calls sqlite3_reset and calls sqlite3_step once. Stepping through all the rows is not necessary when you don't care about the results.

This method finalizes the statement, freeing any resources associated with it.

After a statement has been finalized, it cannot be used for any further queries. Any attempt to run the statement will throw an error. Calling it multiple times will have no effect.

It is a good idea to finalize a statement when you are done with it, but the garbage collector will do it for you if you don't.

import { Database } from "bun:sqlite";

// setup

var db = new Database();

db.run(

"CREATE TABLE foo (id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT, greeting TEXT, count INTEGER)"

);

db.run("INSERT INTO foo (greeting, count) VALUES (?, ?)", "Welcome to bun!", 2);

db.run("INSERT INTO foo (greeting, count) VALUES (?, ?)", "Hello World!", 0);

db.run(

"INSERT INTO foo (greeting, count) VALUES (?, ?)",

"Welcome to bun!!!!",

2

);

// Statement object

var statement = db.query("SELECT * FROM foo WHERE count = ?");

statement.finalize();

// this will throw

statement.run();Calling toString() on a Statement instance prints the expanded SQL query. This is useful for debugging.

import { Database } from "bun:sqlite";

// setup

var db = new Database();

db.run(

"CREATE TABLE foo (id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT, greeting TEXT, count INTEGER)"

);

db.run("INSERT INTO foo (greeting, count) VALUES (?, ?)", "Welcome to bun!", 2);

db.run("INSERT INTO foo (greeting, count) VALUES (?, ?)", "Hello World!", 0);

db.run(

"INSERT INTO foo (greeting, count) VALUES (?, ?)",

"Welcome to bun!!!!",

2

);

// Statement object

const statement = db.query("SELECT * FROM foo WHERE count = ?");

console.log(statement.toString());

// => "SELECT * FROM foo WHERE count = NULL"

statement.run(2); // bind the param

console.log(statement.toString());

// => "SELECT * FROM foo WHERE count = 2"Internally, this calls sqlite3_expanded_sql.

| JavaScript type | SQLite type |

|---|---|

string |

TEXT |

number |

INTEGER or DECIMAL |

boolean |

INTEGER (1 or 0) |

Uint8Array |

BLOB |

Buffer |

BLOB |

bigint |

INTEGER |

null |

NULL |

bun:ffi lets you efficiently call native libraries from JavaScript. It works with languages that support the C ABI (Zig, Rust, C/C++, C#, Nim, Kotlin, etc).

This snippet prints sqlite3's version number:

import { dlopen, FFIType, suffix } from "bun:ffi";

// `suffix` is either "dylib", "so", or "dll" depending on the platform

// you don't have to use "suffix", it's just there for convenience

const path = `libsqlite3.${suffix}`;

const {

symbols: {

// sqlite3_libversion is the function we will call

sqlite3_libversion,

},

} =

// dlopen() expects:

// 1. a library name or file path

// 2. a map of symbols

dlopen(path, {

// `sqlite3_libversion` is a function that returns a string

sqlite3_libversion: {

// sqlite3_libversion takes no arguments

args: [],

// sqlite3_libversion returns a pointer to a string

returns: FFIType.cstring,

},

});

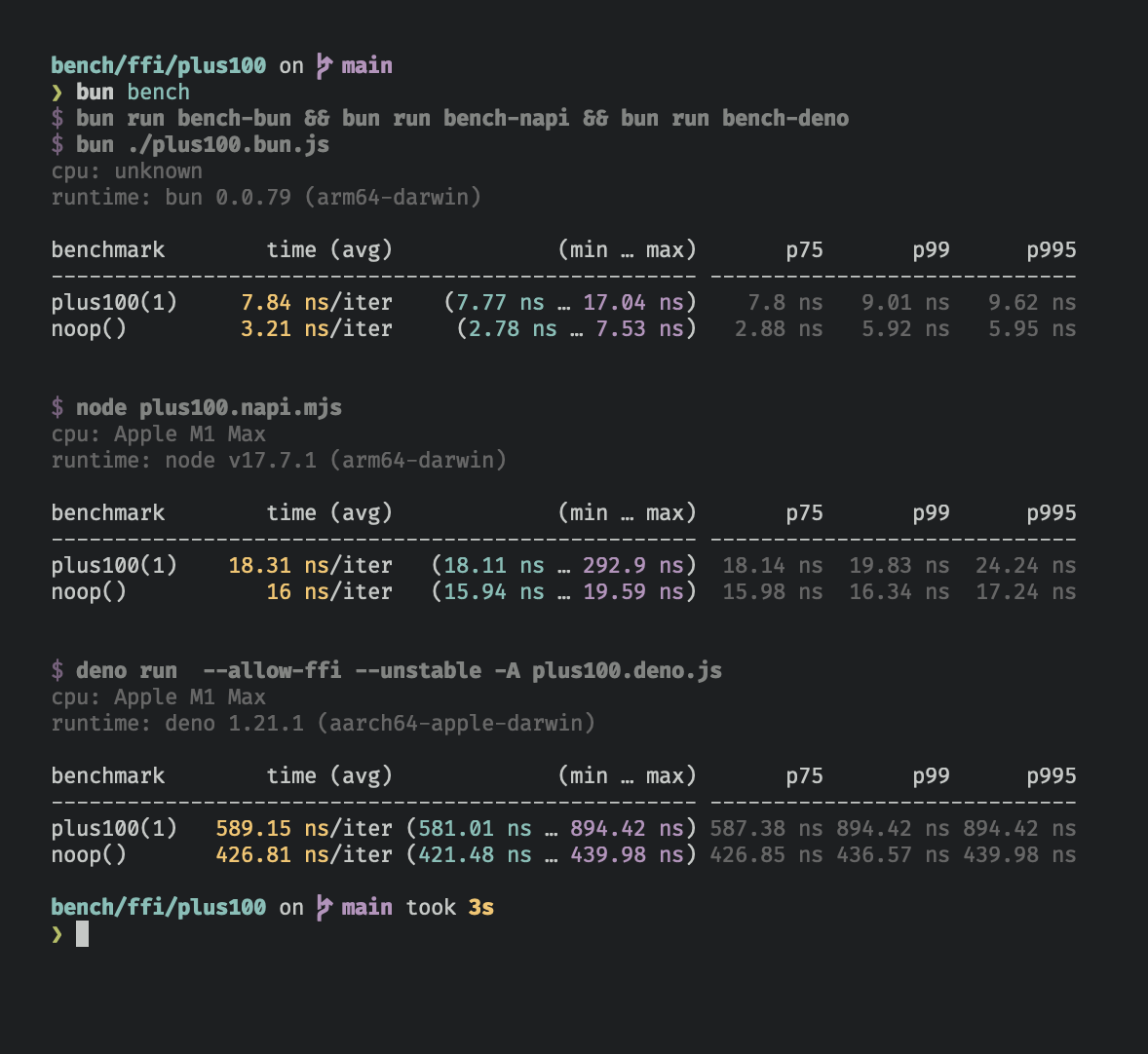

console.log(`SQLite 3 version: ${sqlite3_libversion()}`);3ns to go from JavaScript <> native code with bun:ffi (on my machine, an M1 Pro with 64GB of RAM)

- 5x faster than napi (Node v17.7.1)

- 100x faster than Deno v1.21.1

As measured in this simple benchmark

Why is bun:ffi fast?

Bun generates & just-in-time compiles C bindings that efficiently convert values between JavaScript types and native types.

To compile C, Bun embeds TinyCC, a small and fast C compiler.

With Zig:

// add.zig

pub export fn add(a: i32, b: i32) i32 {

return a + b;

}To compile:

zig build-lib add.zig -dynamic -OReleaseFastPass dlopen the path to the shared library and the list of symbols you want to import.

import { dlopen, FFIType, suffix } from "bun:ffi";

const path = `libadd.${suffix}`;

const lib = dlopen(path, {

add: {

args: [FFIType.i32, FFIType.i32],

returns: FFIType.i32,

},

});

lib.symbols.add(1, 2);With Rust:

// add.rs

#[no_mangle]

pub extern "C" fn add(a: isize, b: isize) -> isize {

a + b

}To compile:

rustc --crate-type cdylib add.rsFFIType |

C Type | Aliases |

|---|---|---|

| cstring | char* |

|

| ptr | void* |

pointer, void*, char* |

| i8 | int8_t |

int8_t |

| i16 | int16_t |

int16_t |

| i32 | int32_t |

int32_t, int |

| i64 | int64_t |

int32_t |

| u8 | uint8_t |

uint8_t |

| u16 | uint16_t |

uint16_t |

| u32 | uint32_t |

uint32_t |

| u64 | uint64_t |

uint32_t |

| f32 | float |

float |

| f64 | double |

double |