| filename | title | layout |

|---|---|---|

06_cellVoltageMeasurement |

Voltage measurement |

main |

The voltage measurement is heavily cost-optimized. Optimization was enabled due to some of the options offered by the processors ADC. For cell voltage measurement no external components are required. Although to achieve the performance needed, this measurement method required some additional software solutions.

The processor has a 10-bit analog-to-digital converter (ADC) and some voltage references. The voltage references are not very accurate, but they are stable, which is important. During the production, it is necessary to calibrate the modules, so the exact value of the voltage reference is known. Typically, an ADC is used by connecting a voltage reference to its reference input and an unknown voltage, we want to measure, to its input. The input voltage we want to measure must always be lower than the reference voltage. In this case, the reference voltage used has an output of 1.5V, because it is the only available reference in the entire processor's power supply range. If this reference voltage were to be connected to the ADC's reference input, the maximum allowed voltage at the input would be less than 1.5V. There lies our problem as we want to measure the voltage range between 1.8V and 5V. The problem could be resolved by using a voltage divider at the ADC's input, but this solution is not acceptable as it has two major drawbacks. Due to the voltage divider, we would introduce additional static energy consumption, undesirable in battery applications. Although this could still be mitigated in some way by using a larger values resistors to limit the current. I think the bigger problem is the cost that two additional resistors would contribute too. The voltage measurement must be accurate to at least ±10mV and the resistors needed to achieve that accuracy are expensive. All of this led me to a different, lesser-known approach of using an ADC. Instead of connecting the reference voltage to the ADC reference input, cell voltage was connected to it. In the case of CarettaBMS, this is also the supply voltage of the processor. This now means that any voltage in the range between 0V and the processor supply can be measured at the ADCs input. It would make sense to connect a known value to the input, such as a voltage reference of 1.5V. The voltage will always be lower than the processor's power supply. This way of measuring has been used many times but is not well known and it's not common. The important thing is that ADC always operates within its own operating parameters.

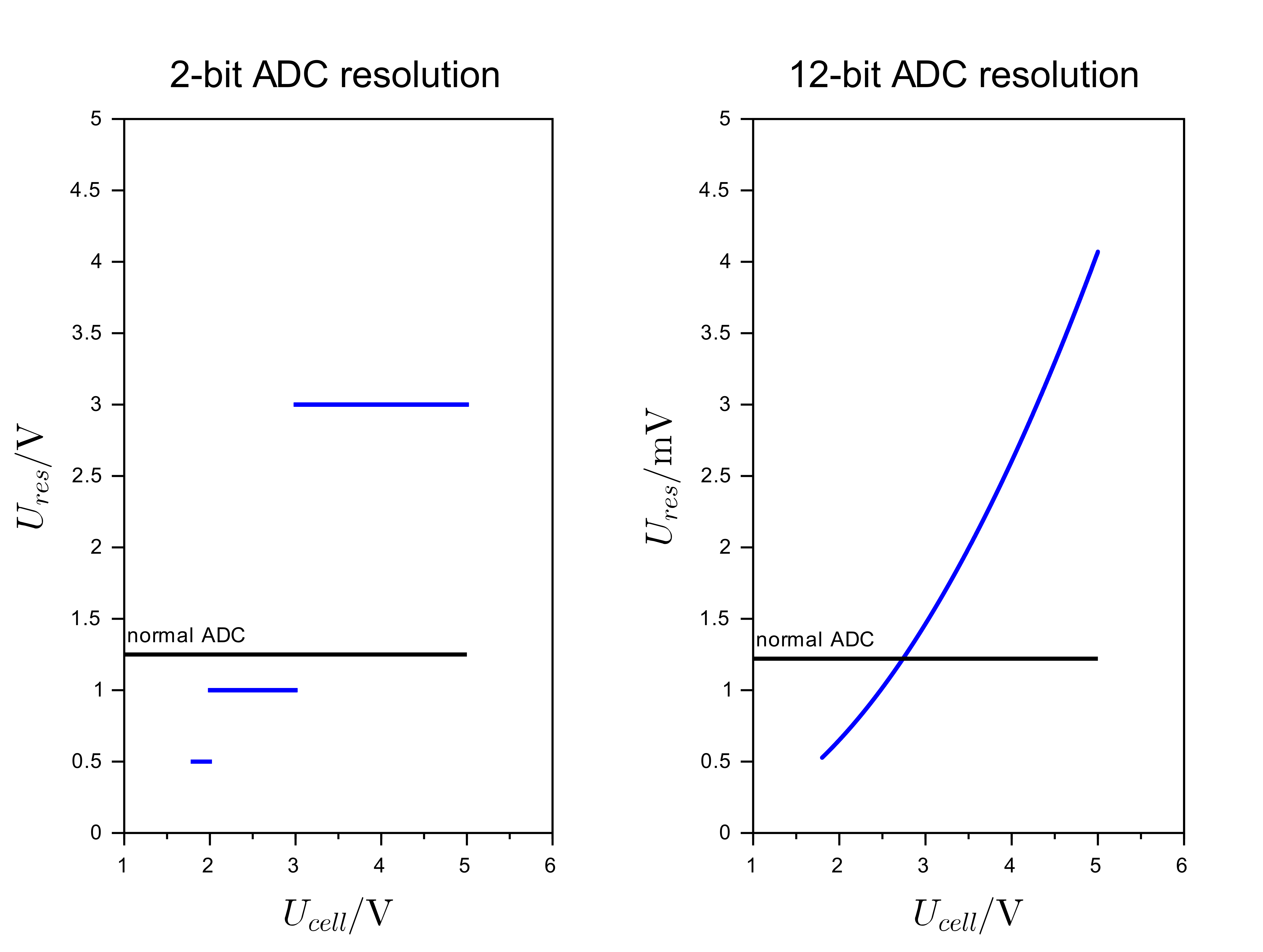

As this ADC configuration use is not widespread or well documented, there is no data on the accuracy and resolution of the measurement. For a BMS, these two are crucial. We need to take a closer look at the equations that describe how the ADC works. Of particular importance is the resolution of the measurement, which turns out to have a significant nonlinear dependence on the cell voltage.

Below equation typically describes the operation of the ADC and is often used to convert the ADC output data back to the input voltage:

We assume that the reference voltage Vref is a constant and we have a constant number of ADC bits (m). Only the ADC result (n) remains in the equation. This gives the classical linear equation, whit the linear dependence of the ADC result on the input voltage. We can also quickly recognize the resolution of the ADC, which is given as a fraction of the reference voltage or Uref / 2^m. Due to the unusual ADC configuration, where the quantities at the inputs of the ADC are swapped, we need to do the same in the previous equation. We get a new equation that describes the operation of the ADC in the current configuration:

We would prefer to rearrange the new equation to be more like the first one because we want to calculate Uin from the ADC result:

By the same analysis as we performed on the first equation, we can replace Uref and m by constants. The measured voltage no longer has a linear dependence on the ADC result. The equation no longer shows us the ADC resolution as the first equation did. Now, the path to the equation that describes the ADC resolution is much more difficult as the resolution changes. The resolution depends on the cell voltage. Briefly, we would summarize that the larger the difference between the reference voltage and the cell voltage, the lower the resolution. To facilitate the derivation of the equation, a simple mathematical model of the ADC was developed, where the two input quantities were replaced (model). The model has contributed greatly to a better understanding of ADC performance. The conclusion is that the resolution of the ADC is equal to the difference between the next ADC result, when we increase the voltage, and the current result. This is also described by the next equation:

We further transform the equation to obtain a single fraction. This gives the equation:

This equation describes how the resolution changes depending on the ADC result. To express the resolution of the ADC as a function of the input voltage Uin, we replace the ADC result (n) in the equation with the second equation. In doing so, we must take into account the property of the quantizer and the ADC result is always a natural number or 0. This is achieved with the floor function and an additional offset factor (o) that defines the operation of the ADC around the result 0. This factor can be 0 or 0.5. In this case, the offset factor is 0.

When all parameters are inserted into the equation, it turns out that the ADC does not have a sufficient number of bits to achieve the sufficient resolution and consequently the accuracy specified in the requirements. However, the use of ADC in the described configuration was chosen because the cost is very important. In this configuration, no external components are required. The resolution problem was later solved in the program by oversampling the ADC, thus achieving the required measurement resolution.