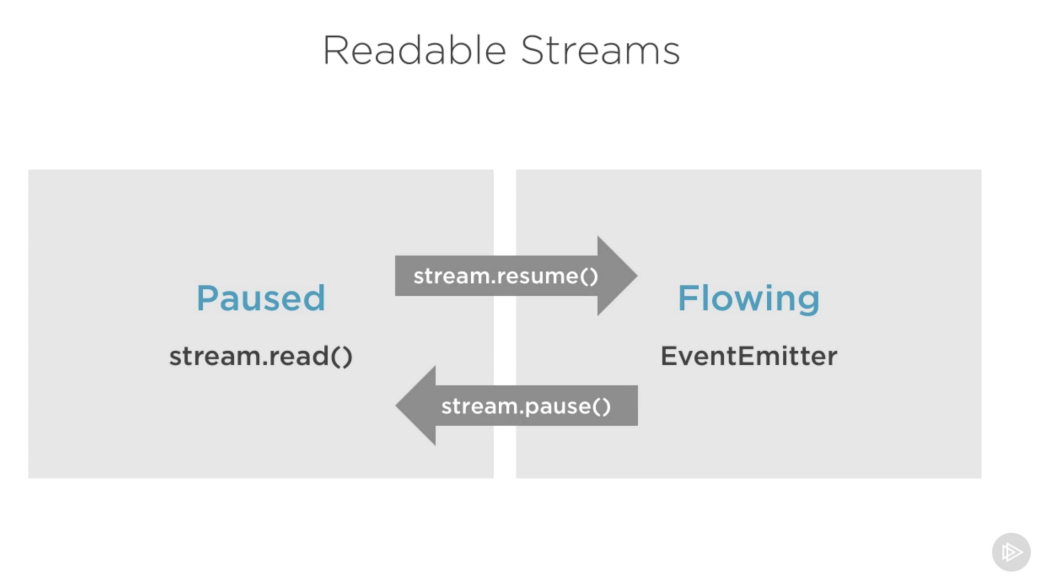

Readable streams have two main modes that affect the way we can consume them:

- They can be either in the paused mode

- Or in the flowing mode

Those modes are sometimes referred to as pull and push modes.

All readable streams start in the paused mode by default but they can be easily switched to flowing and back to paused when needed. Sometimes, the switching happens automatically.

When a readable stream is in the paused mode, we can use the read() method to read from the stream on demand, however, for a readable stream in the flowing mode, the data is continuously flowing and we have to listen to events to consume it.

In the flowing mode, data can actually be lost if no consumers are available to handle it. This is why, when we have a readable stream in flowing mode, we need a data event handler. In fact, just adding a data event handler switches a paused stream into flowing mode and removing the data event handler switches the stream back to paused mode. Some of this is done for backward compatibility with the older Node streams interface.

To manually switch between these two stream modes, you can use the resume() and pause() methods.

When consuming readable streams using the pipe method, we don’t have to worry about these modes as pipe manages them automatically.

When we talk about streams in Node.js, there are two main different tasks:

- The task of implementing the streams.

- The task of consuming them.

So far we’ve been talking about only consuming streams. Let’s implement some!

Stream implementers are usually the ones who require the stream module. We can implement a writable stream in many ways. We can, for example, extend the Writable constructor if we want

const { Writable } = require('stream');

class myWritableStream extends Writable {}

However, I prefer the simpler constructor approach. We just create an object from the Writable constructor and pass it a number of options. The only required option is a write function which exposes the chunk of data to be written.

const { Writable } = require('stream');

const outStream = new Writable({

write(chunk, encoding, callback) {

console.log(chunk.toString());

callback();

}

});

process.stdin.pipe(outStream);

This write method takes three arguments.

- The chunk is usually a buffer unless we configure the stream differently.

- The encoding argument is needed in that case, but usually we can ignore it.

- The callback is a function that we need to call after we’re done processing the data chunk. It’s what signals whether the write was successful or not. To signal a failure, call the callback with an error object.

To consume this stream, we can simply use it with process.stdin, which is a readable stream, so we can just pipe process.stdin into our outStream.

We can just pipe stdin into stdout and we’ll get the exact same echo feature with this single line:

process.stdin.pipe(process.stdout);

To implement a readable stream, we require the Readable interface, and construct an object from it, and implement a read() method in the stream’s configuration parameter:

const { Readable } = require('stream');

const inStream = new Readable({

read() {}

});

There is a simple way to implement readable streams. We can just directly push the data that we want the consumers to consume.

const { Readable } = require('stream');

const inStream = new Readable({

read() {}

});

inStream.push('ABCDEFGHIJKLM');

inStream.push('NOPQRSTUVWXYZ');

inStream.push(null); // No more data

inStream.pipe(process.stdout);

When we push a null object, that means we want to signal that the stream does not have any more data.

We’re basically pushing all the data in the stream before piping it to process.stdout. The much better way is to push data on demand, when a consumer asks for it. We can do that by implementing the read() method in the configuration object.

When the read method is called on a readable stream, the implementation can push partial data to the queue. For example, we can push one letter at a time, starting with character code 65 (which represents A), and incrementing that on every push:

const inStream = new Readable({

read(size) {

this.push(String.fromCharCode(this.currentCharCode++));

if (this.currentCharCode > 90) {

this.push(null);

}

}

});

inStream.currentCharCode = 65;

inStream.pipe(process.stdout);

While the consumer is reading a readable stream, the read method will continue to fire, and we’ll push more letters.

This code is equivalent to the simpler one we started with but now we’re pushing data on demand when the consumer asks for it. You should always do that.

With Duplex streams, we can implement both readable and writable streams with the same object. It’s as if we inherit from both interfaces.

const { Duplex } = require('stream');

const inoutStream = new Duplex({

write(chunk, encoding, callback) {

console.log(chunk.toString());

callback();

},

read(size) {

this.push(String.fromCharCode(this.currentCharCode++));

if (this.currentCharCode > 90) {

this.push(null);

}

}

});

inoutStream.currentCharCode = 65;

process.stdin.pipe(inoutStream).pipe(process.stdout);

By combining the methods, we can use this duplex stream to read the letters from A to Z and we can also use it for its echo feature. We pipe the readable stdin stream into this duplex stream to use the echo feature and we pipe the duplex stream itself into the writable stdout stream to see the letters A through Z.

It’s important to understand that the readable and writable sides of a duplex stream operate completely independently from one another. This is merely a grouping of two features into an object.

A transform stream is the more interesting duplex stream because its output is computed from its input.

For a transform stream, we don’t have to implement the read or write methods, we only need to implement a transform method, which combines both of them. It has the signature of the write method and we can use it to push data as well.

Here’s a simple transform stream which echoes back anything you type into it after transforming it to upper case format:

const { Transform } = require('stream');

const upperCaseTr = new Transform({

transform(chunk, encoding, callback) {

this.push(chunk.toString().toUpperCase());

callback();

}

});

process.stdin.pipe(upperCaseTr).pipe(process.stdout);

Node has a few very useful built-in transform streams. Namely, the zlib and crypto streams.

Here’s an example that uses the zlib.createGzip() stream combined with the fs readable/writable streams to create a file-compression script:

const fs = require('fs');

const zlib = require('zlib');

const file = process.argv[2];

fs.createReadStream(file)

.pipe(zlib.createGzip())

.pipe(fs.createWriteStream(file + '.gz'));

You can use this script to gzip any file you pass as the argument. We’re piping a readable stream for that file into the zlib built-in transform stream and then into a writable stream for the new gzipped file.

The cool thing about using pipes is that we can actually combine them with events if we need to. Say, for example, I want the user to see a progress indicator while the script is working and a “Done” message when the script is done. Since the pipe method returns the destination stream, we can chain the registration of events handlers as well:

const fs = require('fs');

const zlib = require('zlib');

const file = process.argv[2];

fs.createReadStream(file)

.pipe(zlib.createGzip())

.on('data', () => process.stdout.write('.'))

.pipe(fs.createWriteStream(file + '.zz'))

.on('finish', () => console.log('Done'));

What’s great about the pipe method though is that we can use it to compose our program piece by piece, in a much readable way. For example, instead of listening to the data event above, we can simply create a transform stream to report progress, and replace the .on() call with another .pipe() call:

const fs = require('fs');

const zlib = require('zlib');

const file = process.argv[2];

const { Transform } = require('stream');

const reportProgress = new Transform({

transform(chunk, encoding, callback) {

process.stdout.write('.');

callback(null, chunk);

}

});

fs.createReadStream(file)

.pipe(zlib.createGzip())

.pipe(reportProgress)

.pipe(fs.createWriteStream(file + '.zz'))

.on('finish', () => console.log('Done'));

This reportProgress stream is a simple pass-through stream, but it reports the progress to standard out as well. Note how I used the second argument in the callback() function to push the data inside the transform() method. This is equivalent to pushing the data first.

For example, if we need to encrypt the file before or after we gzip it, all we need to do is pipe another transform stream in that exact order that we needed. We can use Node’s crypto module for that:

const crypto = require('crypto');

// ...

fs.createReadStream(file)

.pipe(zlib.createGzip())

.pipe(crypto.createCipher('aes192', 'a_secret'))

.pipe(reportProgress)

.pipe(fs.createWriteStream(file + '.zz'))

.on('finish', () => console.log('Done'));

The script above compresses and then encrypts the passed file and only those who have the secret can use the outputted file. We can’t unzip this file with the normal unzip utilities because it’s encrypted.

To actually be able to unzip anything zipped with the script above, we need to use the opposite streams for crypto and zlib in a reverse order, which is simple:

fs.createReadStream(file)

.pipe(crypto.createDecipher('aes192', 'a_secret'))

.pipe(zlib.createGunzip())

.pipe(reportProgress)

.pipe(fs.createWriteStream(file.slice(0, -3)))

.on('finish', () => console.log('Done'));