In this Unit we will cover the technical practices of flow. Flow is our ability to keep work moving from the left (development) to the right (customer) as quickly as possible. There are a number of practices that we can adopt to increase flow in our environment; however, we will start by looking at the psychology of flow.

- Explain the psychology of flow.

- Describe good deployment pipeline practice.

- Describe good testing practices for flow.

- Describe release methods to encourage flow.

The concept of Flow was initially defined by Mihály Csíkszentmihályi. A Flow state involves the following six characteristics (taken from Wikipedia):

- Intense and focused concentration on the present moment.

- Merging of action and awareness

- A loss of reflective self-consciousness

- A sense of personal control or agency over the situation or activity

- A distortion of temporal experience, one's subjective experience of time is altered

- Experience of the activity as intrinsically rewarding.

Another three identified components are:

- Receiving immediate feedback.

- Feeling that you have the potential to succeed.

- Feeling so engrossed in the experience, that other needs become negligible.

The following diagram illustrates how flow features when mapped to skill level against challenge level.

By w:User:Oliverbeatson - w:File:Challenge vs skill.jpg, Public Domain, Link

- Reflect on your own experiences when you might have experienced flow (playing video games is one known area for example).

- Reflect on which of the mental states as illustrated above you might have been in during the following tasks:

- Attending a lecture.

- Watching a movie.

- Working on a lab for university.

- Working on a coursework for university.

- Doing an exam for university.

A further seven conditions of flow (taken from Wikipedia) are:

- Knowing what to do.

- Knowing how to do it.

- Knowing how well you are doing.

- Knowing where to go (if navigation is involved).

- High perceived challenges.

- High perceived skills.

- Freedom from distractions.

These seven are more inline with our thinking in the module, incorporating DevOps, Scrum, and general lean-agile ideas:

- We need to know what to do, via clear information and agreement with the team (e.g., we understand the user story).

- We know how to do the work, again via information and agreement with the team (e.g., user story) and our skillset.

- Knowing how well we are doing comes from the feedback we get from the system.

- Is not relevant from a navigation point of view, but we do have clear ideas of the direction of work from our Sprint planning and reviews.

- High perceived challenges is basically stretching your capabilities as a developer.

- High perceived skills is about you continuously learning and improving.

- Freedom from distractions means only working on one item at a time. It also means not being distracted via external factors such as your phone during a lecture!

In this module we are slowly building a deployment pipeline. In the real world, you would do so at the start of the project. However, as you are learning in the module, we are taking our time and not necessarily doing things in the best manner to start with.

A key factor we are working on is the use of version control. We have been submitting almost everything to version control, as this ensures we can recreate the entire production environment from version control. This is good practice in modern software development.

We want developers to run production-like environments on their own workstations. The "it runs on my laptop" excuse should not be acceptable.

For example, we use containers and deploy to the cloud. Developers can run and test their code in production-like environments as part of their daily work by using these same containers.

We should ensure all parts of out software system are shared in VCS so they can be easily recreated. For example, code, database, configuration (Docker), tests, etc. can all be in version control. It is not sufficient just to recreate previous state. We nee to be able to recreate entire build processes.

This is where operations really comes in. We need to use automated configuration systems (e.g., Puppet, Ansible, etc.) which only require text files. This is "configuration as code".

Furthermore, we create new VMs or containers and deploy them, destroying the old ones. This is known as immutable infrastructure - no manual changes to infrastructure. It must be rebuilt from VCS.

Step 4: Modify our Definition of Development "Done" to Include Running in Production-like Environments

We introduced Definition of Done (DoD) in Unit 01 (b): Forming Scrum Teams. DoD needs to go beyond just having correct code. For each development increment, our code must be:

- Integrated.

- Tested.

- Working and potentially shippable.

- Demonstrated in production-like environment.

This prevents a feature being called done because it ran on a developer's machine and nowhere else.

Without automated testing larger code bases cost more to test. This is unscalable. Developers become afraid to commit changes. New team members don't understand the code. Existing team members understand too well the problems in the system that will cause problems when changes occur.

In 2013, due to Google's automated testing and integration approach, 4000 teams of developers were changing 50% of their code per month. Also:

- 40,000 code commits per day.

- 50,000 builds per day, sometimes up to 90,000.

- 120,000 automated test suites.

- 75 million test cases per day.

Build quality into our product at the earliest stage by developers building automated tests as part of daily work.

Taken from Continuous Delivery by Humble and Farley.

Commit Stage builds and packages software, runs unit tests, static analysis, etc. Acceptance Stage deploys into production-like environment for automated acceptance tests.

Continuous integration practices require three capabilities:

- comprehensive and reliable set of automated tests to validate software is deployable.

- culture to stop the entire production line when validation tests fail.

- developers working in small batches on trunk rather than long-lived feature branches.

We will examine Continuous Integration in Unit 8b and Continuous Delivery in Unit 8a.

Three types of automated test:

- Unit tests which we cover in Unit 7b.

- Acceptance tests to check software operates as designed - does it do what the customer wants?

- Integration tests to check application interacts with other applications and services correctly.

It is quite reasonable for software to take ten-minutes to build and test locally.

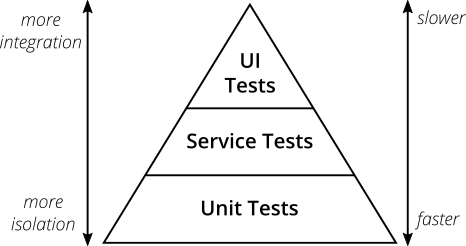

The Test Pyramid allows us to understand the cost and level of our tests.

Taken from Martin Fowler, The Practical Test Pyramid https://martinfowler.com/articles/practical-test-pyramid.html

- Read Martin Fowler's post on The Practical Test Pyramid for a deeper understanding of test automation.

The Test Pyramid has three levels:

- UI tests which are slow (expensive) but allow us to test a fully integrated system.

- Service tests are the midway point in speed and integration.

- Unit tests provide the least integration, but are fast.

Basically, if there are tests that can be run at the same time, do so.

Taken from Continuous Delivery by Humble and Farley.

Begin every change to the system by writing the automated test to test the expected behaviour. Test fails, and we write code to pass the test. This is Test Driven Development.

Three steps of Test-Driven Development:

- Ensure the test fail. Write a test for the functionality to add. Commit.

- Ensure the test passes. Write the code to pass the test. Commit.

- Refactor old and new code to make it well structured. Ensure test still passes. Commit.

Having humans executing tests that can be automated is a waste of human potential. To start, build a small number of automated tests and grow them over time, increasing the level of assurance that we can quickly detect changes to the system that break the build.

Performance testing is a whole subject in itself. We need to know our application works under stress, and so we need to build a specialist environment to stress test the application. Build the performance testing environment at the start of the project.

Non-functional requirements typically include security, scalability, and availability concerns (as well as others). These can normally be managed via correct configuration and suitable management of the configuration.

When our deployment pipeline breaks, at a minimum we notify the entire team of the failure so anyone can fix the problem or we can rollback the build. Why do we need to pull the Andon Cord? If not, we end up with an unpredictable "stabilization phase" where the team is doing fixes to get the tests to pass, accumulating technical debt, and effectively back in a waterfall method.

The longer developers work in isolated branches the more difficult it becomes to integrate and merge everyone together. If merging code is painful, we will do it less often, making the problem worse over time. Our practice should be:

- Multiple builds per day.

- Multiple commits per day.

- 1000s of new lines of code per day.

This is different than single builds, commits, and a few lines of code per day seen in rigid organisations.

We discussed small batch sizes in Unit 3b. We used the following image:

If merging is difficult, we don't do it. Then we don't do refactoring work to improve code quality, which leads to an ongoing build-up of technical debt. A lack of refactoring means normal changes become difficult over time, slowing down the rate of new feature development.

There are two ends to the spectrum of working with branches:

- Optimise for individual productivity - bad as collaboration becomes extremely difficult. Everyone only sees their own problems.

- Optimise for team productivity - better as everyone sees everything. A single commit can break everything though, and stop progress.

To do better we need to reduce the work of a merge. All developers commit to develop at least once per-day. This reduces batch size to the work of a developer per day. More frequent check-ins lead to smaller batch sizes and better single-piece flow.

We can have gated commits - if the commit breaks deployment then reject it. Then the team swarm to solve the problem.

Our Definition of Done now becomes (from The DevOps Handbook):

At the end of each development interval, we must have integrated, tested, working, and potentially shippable code, demonstrated in a production-like environment, created from develop using a one-click process, and validated with automated tests.

If we can get our releases to be low-risk, we will perform more of them. This is the definition of flow: releasing value quickly to the customer.

Developers need to be able to deploy code to achieve fast, low-risk releases. For example, at Facebook deploys were simplified to support the growth in developer numbers:

Taken from Ship Early and Ship Twice as Often: https://www.facebook.com/notes/facebook-engineering/ship-early-and-ship-twice-as-often/10150985860363920/

Deployment should be automated. The deployment process and steps involved must be fully documented. Then we can simplify and automate the manual steps, such as:

- Packaging code for deployment.

- Creating virtual machines and containers.

- Deployment of middleware.

- Copying to production servers.

- Restarting servers, applications, or services.

- Generating configuration files from templates.

- Running test procedures.

Our deployment pipeline should:

- Deploy the same build to every environment.

- Smoke test (sanity check core functionality) our deployments.

- Ensure environments are consistent.

The goal is to go from commit to deployment in a single step. Developers can commit and it appears directly in deployment if checks are passed. This affects following stages:

- Build - create packages from version control to deploy.

- Test - anyone able to run test suite.

- Deploy - execute script in version control.

First, we must ensure packages created during continuous integration are suitable for deployment. Then we provide a push-button, self-service deployment to the developers.

Self-service deployments like this requires more information to development and operations. We need to show the readiness of production environments at a glance. For audit reasons, we need to record automatically which commands were run when, where, and by who. Also, we need to run smoke tests on the deployment machine to ensure everything is correct. All of these provide fast-feedback so developers know if a deploy was successful.

Deployments and releases have different motivations. A deployment is the installation of a specified version of the software. It can be continuously done to ensure software is of the highest quality. A release is a feature (or set of features) made available to the customer. It requires deployment, but is normally defined via marketing or sales agreements with customers.

There are different manners to release software: environment-based and application-based.

We can run two sets of servers, called the Blue-green deployment pattern:

Our databases can also follow blue-green deployment, or we can decouple database changes from application changes.

We can also use the Canary Pattern where we deploy first to internal customers, then a sub-set of external customers, then finally full-deployment. If any point goes wrong, we roll-back.

There are two methods to release an application then test and activate features over time. First we can use Feature Toggles. A feature toggle simply allows us to switch off features in a deployed application, for example via a compiler flag.

Dark launches are similar, but allow developers and testers to experiment with the code while it is hidden from the customer.

We covered modern software architecture in Unit 3a. Microservice architectures enable small batch sizes, thus supporting flow.

- We've explained the psychology of flow, and specifically mapped that back to some of the ideas we have introduced around Scrum, DevOps, and lean/agile.

- We've described good deployment pipeline practice, discussing ideas around version control and rebuilding infrastructure.

- We've describe good testing practices for flow, focusing on test automation which we cover in more detail later in the module.

- We've described release methods to encourage flow, and in particular the difference between deploying and releasing.

The goto book on DevOps if The DevOps Handbook: How to Create World-class Agility, Reliability & Security in Technology Organisations by Gene Kim, Jez Humble, Patrick Debois, and John Willis.