| title | thumbnail | authors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Let's talk about biases in machine learning! Ethics and Society Newsletter #2 |

/blog/assets/122_ethics_soc_2/thumbnail-solstice.png |

|

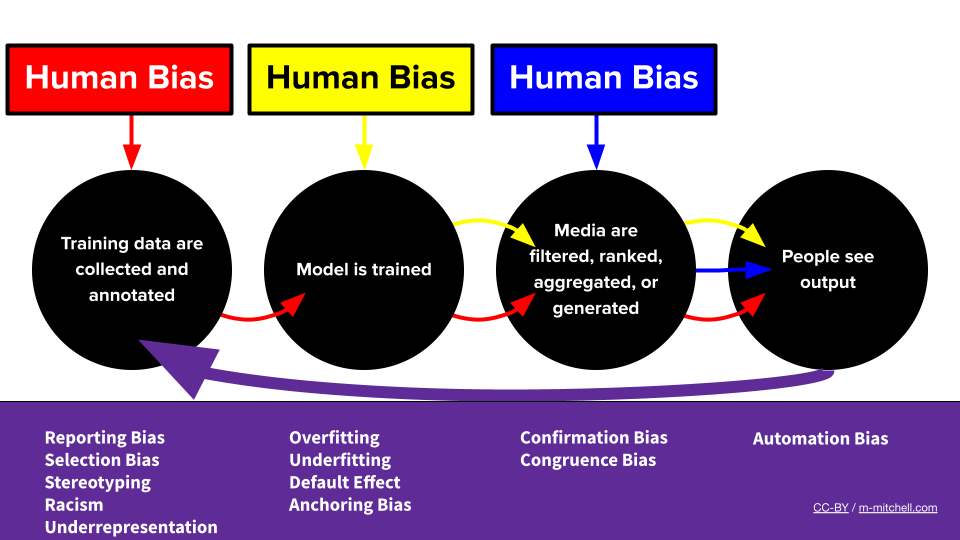

Bias in ML is ubiquitous, and Bias in ML is complex; so complex in fact that no single technical intervention is likely to meaningfully address the problems it engenders. ML models, as sociotechnical systems, amplify social trends that may exacerbate inequities and harmful biases in ways that depend on their deployment context and are constantly evolving.

This means that developing ML systems with care requires vigilance and responding to feedback from those deployment contexts, which in turn we can facilitate by sharing lessons across contexts and developing tools to analyze signs of bias at every level of ML development.

This blog post from the Ethics and Society regulars @🤗 shares some of the lessons we have learned along with tools we have developed to support ourselves and others in our community’s efforts to better address bias in Machine Learning. The first part is a broader reflection on bias and its context. If you’ve already read it and are coming back specifically for the tools, feel free to jump to the datasets or models section!

Table of contents:

- On Machine Biases

- Tools and Recommendations

ML systems allow us to automate complex tasks at a scale never seen before as they are deployed in more sectors and use cases. When the technology works at its best, it can help smooth interactions between people and technical systems, remove the need for highly repetitive work, or unlock new ways of processing information to support research.

These same systems are also likely to reproduce discriminatory and abusive behaviors represented in their training data, especially when the data encodes human behaviors. The technology then has the potential to make these issues significantly worse. Automation and deployment at scale can indeed:

- lock in behaviors in time and hinder social progress from being reflected in technology,

- spread harmful behaviors beyond the context of the original training data,

- amplify inequities by overfocusing on stereotypical associations when making predictions,

- remove possibilities for recourse by hiding biases inside “black-box” systems.

In order to better understand and address these risks, ML researchers and developers have started studying machine bias or algorithmic bias, mechanisms that might lead systems to, for example, encode negative stereotypes or associations or to have disparate performance for different population groups in their deployment context.

These issues are deeply personal for many of us ML researchers and developers at Hugging Face and in the broader ML community. Hugging Face is an international company, with many of us existing between countries and cultures. It is hard to fully express our sense of urgency when we see the technology we work on developed without sufficient concern for protecting people like us; especially when these systems lead to discriminatory wrongful arrests or undue financial distress and are being increasingly sold to immigration and law enforcement services around the world. Similarly, seeing our identities routinely suppressed in training datasets or underrepresented in the outputs of “generative AI” systems connects these concerns to our daily lived experiences in ways that are simultaneously enlightening and taxing.

While our own experiences do not come close to covering the myriad ways in which ML-mediated discrimination can disproportionately harm people whose experiences differ from ours, they provide an entry point into considerations of the trade-offs inherent in the technology. We work on these systems because we strongly believe in ML’s potential — we think it can shine as a valuable tool as long as it is developed with care and input from people in its deployment context, rather than as a one-size-fits-all panacea. In particular, enabling this care requires developing a better understanding of the mechanisms of machine bias across the ML development process, and developing tools that support people with all levels of technical knowledge of these systems in participating in the necessary conversations about how their benefits and harms are distributed.

The present blog post from the Hugging Face Ethics and Society regulars provides an overview of how we have worked, are working, or recommend users of the HF ecosystem of libraries may work to address bias at the various stages of the ML development process, and the tools we develop to support this process. We hope you will find it a useful resource to guide concrete considerations of the social impact of your work and can leverage the tools referenced here to help mitigate these issues when they arise.

The first and maybe most important concept to consider when dealing with machine bias is context. In their foundational work on bias in NLP, Su Lin Blodgett et al. point out that: “[T]he majority of [academic works on machine bias] fail to engage critically with what constitutes “bias” in the first place”, including by building their work on top of “unstated assumptions about what kinds of system behaviors are harmful, in what ways, to whom, and why”.

This may not come as much of a surprise given the ML research community’s focus on the value of “generalization” — the most cited motivation for work in the field after “performance”. However, while tools for bias assessment that apply to a wide range of settings are valuable to enable a broader analysis of common trends in model behaviors, their ability to target the mechanisms that lead to discrimination in concrete use cases is inherently limited. Using them to guide specific decisions within the ML development cycle usually requires an extra step or two to take the system’s specific use context and affected people into consideration.

Now let’s dive deeper into the issue of linking biases in stand-alone/context-less ML artifacts to specific harms. It can be useful to think of machine biases as risk factors for discrimination-based harms. Take the example of a text-to-image model that over-represents light skin tones when prompted to create a picture of a person in a professional setting, but produces darker skin tones when the prompts mention criminality. These tendencies would be what we call machine biases at the model level. Now let’s think about a few systems that use such a text-to-image model:

- The model is integrated into a website creation service (e.g. SquareSpace, Wix) to help users generate backgrounds for their pages. The model explicitly disables images of people in the generated background.

- In this case, the machine bias “risk factor” does not lead to discrimination harm because the focus of the bias (images of people) is absent from the use case.

- Further risk mitigation is not required for machine biases, although developers should be aware of ongoing discussions about the legality of integrating systems trained on scraped data in commercial systems.

- The model is integrated into a stock images website to provide users with synthetic images of people (e.g. in professional settings) that they can use with fewer privacy concerns, for example, to serve as illustrations for Wikipedia articles

- In this case, machine bias acts to lock in and amplify existing social biases. It reinforces stereotypes about people (“CEOs are all white men”) that then feed back into complex social systems where increased bias leads to increased discrimination in many different ways (such as reinforcing implicit bias in the workplace).

- Mitigation strategies may include educating the stock image users about these biases, or the stock image website may curate generated images to intentionally propose a more diverse set of representations.

- The model is integrated into a “virtual sketch artist” software marketed to police departments that will use it to generate pictures of suspects based on verbal testimony

- In this case, the machine biases directly cause discrimination by systematically directing police departments to darker-skinned people, putting them at increased risk of harm including physical injury and unlawful imprisonment.

- In cases like this one, there may be no level of bias mitigation that makes the risk acceptable. In particular, such a use case would be closely related to face recognition in the context of law enforcement, where similar bias issues have led several commercial entities and legislatures to adopt moratoria pausing or banning its use across the board.

So, who’s on the hook for machine biases in ML? These three cases illustrate one of the reasons why discussions about the responsibility of ML developers in addressing bias can get so complicated: depending on decisions made at other points in the ML system development process by other people, the biases in an ML dataset or model may land anywhere between being irrelevant to the application settings and directly leading to grievous harm. However, in all of these cases, stronger biases in the model/dataset increase the risk of negative outcomes. The European Union has started to develop frameworks that address this phenomenon in recent regulatory efforts: in short, a company that deploys an AI system based on a measurably biased model is liable for harm caused by the system.

Conceptualizing bias as a risk factor then allows us to better understand the shared responsibility for machine biases between developers at all stages. Bias can never be fully removed, not least because the definitions of social biases and the power dynamics that tie them to discrimination vary vastly across social contexts. However:

- Each stage of the development process, from task specification, dataset curation, and model training, to model integration and system deployment, can take steps to minimize the aspects of machine bias** that most directly depend on its choices** and technical decisions, and

- Clear communication and information flow between the various ML development stages can make the difference between making choices that build on top of each other to attenuate the negative potential of bias (multipronged approach to bias mitigation, as in deployment scenario 1 above) versus making choices that compound this negative potential to exacerbate the risk of harm (as in deployment scenario 3).

In the next section, we review these various stages along with some of the tools that can help us address machine bias at each of them.

Ready for some practical advice yet? Here we go 🤗

There is no one single way to develop ML systems; which steps happen in what order depends on a number of factors including the development setting (university, large company, startup, grassroots organization, etc…), the modality (text, tabular data, images, etc…), and the preeminence or scarcity of publicly available ML resources. However, we can identify three common stages of particular interest in addressing bias. These are the task definition, the data curation, and the model training. Let’s have a look at how bias handling may differ across these various stages.

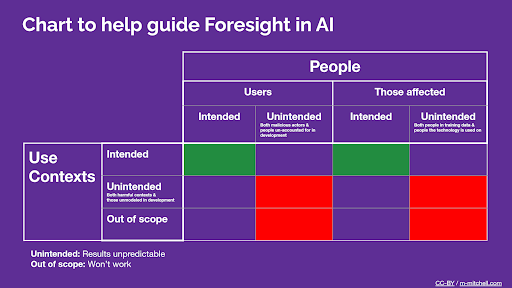

Whether and to what extent bias in the system concretely affects people ultimately depends on what the system is used for. As such, the first place developers can work to mitigate bias is when deciding how ML fits in their system, e.g., by deciding what optimization objective it will use.

For example, let’s go back to one of the first highly-publicized cases of a Machine Learning system used in production for algorithmic content recommendation. From 2006 to 2009, Netflix ran the Netflix Prize, a competition with a 1M$ cash prize challenging teams around the world to develop ML systems to accurately predict a user’s rating for a new movie based on their past ratings. The winning submission improved the RMSE (Root-mean-square-error) of predictions on unseen user-movie pairs by over 10% over Netflix’s own CineMatch algorithm, meaning it got much better at predicting how users would rate a new movie based on their history. This approach opened the door for much of modern algorithmic content recommendation by bringing the role of ML in modeling user preferences in recommender systems to public awareness.

So what does this have to do with bias? Doesn’t showing people content that they’re likely to enjoy sound like a good service from a content platform? Well, it turns out that showing people more examples of what they’ve liked in the past ends up reducing the diversity of the media they consume. Not only does it lead users to be less satisfied in the long term, but it also means that any biases or stereotypes captured by the initial models — such as when modeling the preferences of Black American users or dynamics that systematically disadvantage some artists — are likely to be reinforced if the model is further trained on ongoing ML-mediated user interactions. This reflects two of the types of bias-related concerns we’ve mentioned above: the training objective acts as a risk factor for bias-related harms as it makes pre-existing biases much more likely to show up in predictions, and the task framing has the effect of locking in and exacerbating past biases.

A promising bias mitigation strategy at this stage has been to reframe the task to explicitly model both engagement and diversity when applying ML to algorithmic content recommendation. Users are likely to get more long-term satisfaction and the risk of exacerbating biases as outlined above is reduced!

This example serves to illustrate that the impact of machine biases in an ML-supported product depends not just on where we decide to leverage ML, but also on how ML techniques are integrated into the broader technical system, and with what objective. When first investigating how ML can fit into a product or a use case you are interested in, we first recommend looking for the failure modes of the system through the lens of bias before even diving into the available models or datasets - which behaviors of existing systems in the space will be particularly harmful or more likely to occur if bias is exacerbated by ML predictions?

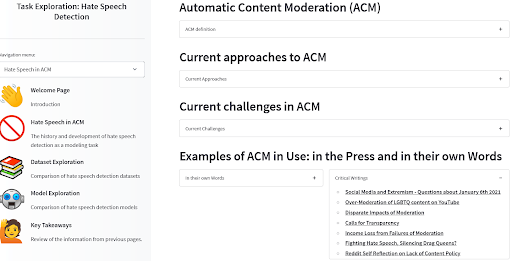

We built a tool to take users through these questions in another case of algorithmic content management: hate speech detection in automatic content moderation. We found for example that looking through news and scientific articles that didn’t particularly focus on the ML part of the technology was already a great way to get a sense of where bias is already at play. Definitely go have a look for an example of how the models and datasets fit with the deployment context and how they can relate to known bias-related harms!

There are as many ways for the ML task definition and deployment to affect the risk of bias-related harms as there are applications for ML systems. As in the examples above, some common steps that may help decide whether and how to apply ML in a way that minimizes bias-related risk include:

- Investigate:

- Reports of bias in the field pre-ML

- At-risk demographic categories for your specific use case

- Examine:

- The impact of your optimization objective on reinforcing biases

- Alternative objectives that favor diversity and positive long-term impacts

While training datasets are not the sole source of bias in the ML development cycle, they do play a significant role. Does your dataset disproportionately associate biographies of women with life events but those of men with achievements? Those stereotypes are probably going to show up in your full ML system! Does your voice recognition dataset only feature specific accents? Not a good sign for the inclusivity of technology you build with it in terms of disparate performance! Whether you’re curating a dataset for ML applications or selecting a dataset to train an ML model, finding out, mitigating, and communicating to what extent the data exhibits these phenomena are all necessary steps to reducing bias-related risks.

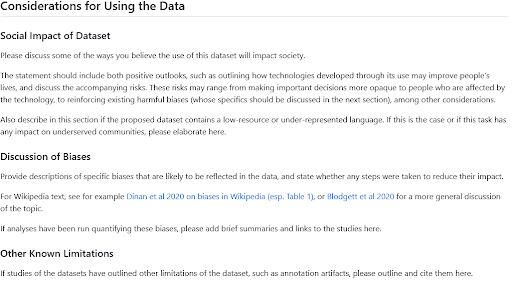

You can usually get a pretty good sense of likely biases in a dataset by reflecting on where it comes from, who are the people represented on the data, and what the curation process was. Several frameworks for this reflection and documentation have been proposed such as Data Statements for NLP or Datasheets for Datasets. The Hugging Face Hub includes a Dataset Card template and guide inspired by these works; the section on considerations for using the data is usually a good place to look for information about notable biases if you’re browsing datasets, or to write a paragraph sharing your insights on the topic if you’re sharing a new one. And if you’re looking for more inspiration on what to put there, check out these sections written by Hub users in the BigLAM organization for historical datasets of legal proceedings, image classification, and newspapers.

While describing the origin and context of a dataset is always a good starting point to understand the biases at play, quantitatively measuring phenomena that encode those biases can be just as helpful. If you’re choosing between two different datasets for a given task or choosing between two ML models trained on different datasets, knowing which one better represents the demographic makeup of your ML system’s user base can help you make an informed decision to minimize bias-related risks. If you’re curating a dataset iteratively by filtering data points from a source or selecting new sources of data to add, measuring how these choices affect the diversity and biases present in your overall dataset can make it safer to use in general.

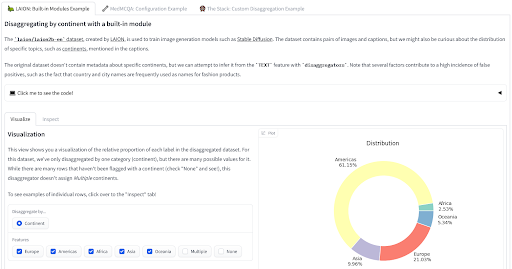

We’ve recently released two tools you can leverage to measure your data through a bias-informed lens. The disaggregators🤗 library provides utilities to quantify the composition of your dataset, using either metadata or leveraging models to infer properties of data points. This can be particularly useful to minimize risks of bias-related representation harms or disparate performances of trained models. Look at the demo to see it applied to the LAION, MedMCQA, and The Stack datasets!

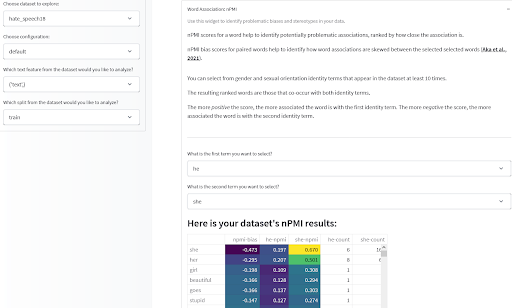

Once you have some helpful statistics about the composition of your dataset, you’ll also want to look at associations between features in your data items, particularly at associations that may encode derogatory or otherwise negative stereotypes. The Data Measurements Tool we originally introduced last year allows you to do this by looking at the normalized Pointwise Mutual Information (nPMI) between terms in your text-based dataset; particularly associations between gendered pronouns that may denote gendered stereotypes. Run it yourself or try it here on a few pre-computed datasets!

These tools aren’t full solutions by themselves, rather, they are designed to support critical examination and improvement of datasets through several lenses, including the lens of bias and bias-related risks. In general, we encourage you to keep the following steps in mind when leveraging these and other tools to mitigate bias risks at the dataset curation/selection stage:

- Identify:

- Aspects of the dataset creation that may exacerbate specific biases

- Demographic categories and social variables that are particularly important to the dataset’s task and domain

- Measure:

- The demographic distribution in your dataset

- Pre-identified negative stereotypes represented

- Document:

- Share what you’ve Identified and Measured in your Dataset Card so it can benefit other users, developers, and otherwise affected people

- Adapt:

- By choosing the dataset least likely to cause bias-related harms

- By iteratively improving your dataset in ways that reduce bias risks

Similar to the dataset curation/selection step, documenting and measuring bias-related phenomena in models can help both ML developers who are selecting a model to use as-is or to finetune and ML developers who want to train their own models. For the latter, measures of bias-related phenomena in the model can help them learn from what has worked or what hasn’t for other models and serve as a signal to guide their own development choices.

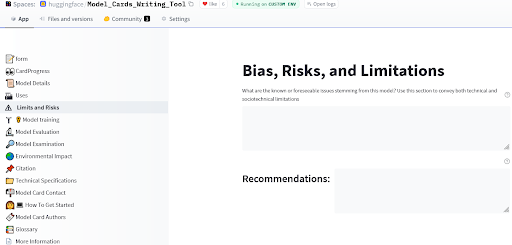

Model cards were originally proposed by (Mitchell et al., 2019) and provide a framework for model reporting that showcases information relevant to bias risks, including broad ethical considerations, disaggregated evaluation, and use case recommendation. The Hugging Face Hub provides even more tools for model documentation, with a model card guidebook in the Hub documentation, and an app that lets you create extensive model cards easily for your new model.

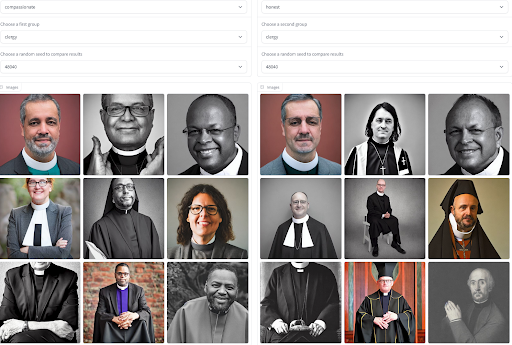

Documentation is a great first step for sharing general insights about a model’s behavior, but it is usually static and presents the same information to all users. In many cases, especially for generative models that can generate outputs to approximate the distribution of their training data, we can gain a more contextual understanding of bias-related phenomena and negative stereotypes by visualizing and contrasting model outputs. Access to model generations can help users bring intersectional issues in the model behavior corresponding to their lived experience, and evaluate to what extent a model reproduces gendered stereotypes for different adjectives. To facilitate this process, we built a tool that lets you compare generations not just across a set of adjectives and professions, but also across different models! Go try it out to get a sense of which model might carry the least bias risks in your use case.

Visualize Adjective and Occupation Biases in Image Generation by Sasha

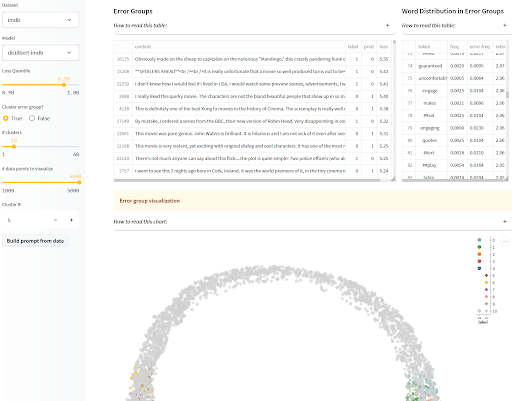

Visualization of model outputs isn’t just for generative models though! For classification models, we also want to look out for bias-related harms caused by a model’s disparate performance on different demographics. If you know what protected classes are most at risk of discrimination and have those annotated in an evaluation set, then you can report disaggregated performance over the different categories in your model card as mentioned above, so users can make informed decisions. If however, you are worried that you haven’t identified all populations at risk of bias-related harms, or if you do not have access to annotated test examples to measure the biases you suspect, that’s where interactive visualizations of where and how the model fails come in handy! To help you with this, the SEAL app groups similar mistakes by your model and shows you some common features in each cluster. If you want to go further, you can even combine it with the disaggregators library we introduced in the datasets section to find clusters that are indicative of bias-related failure modes!

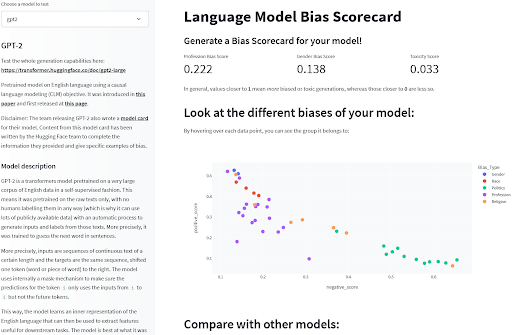

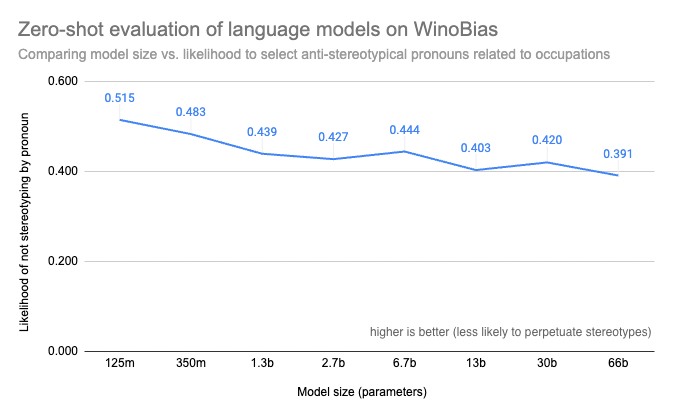

Finally, a few benchmarks exist that can measure bias-related phenomena in models. For language models, benchmarks such as BOLD, HONEST, or WinoBias provide quantitative evaluations of targeted behaviors that are indicative of biases in the models. While the benchmarks have their limitations, they do provide a limited view into some pre-identified bias risks that can help describe how the models function or choose between different models. You can find these evaluations pre-computed on a range of common language models in this exploration Space to get a first sense of how they compare!

Even with access to a benchmark for the models you are considering, you might find that running evaluations of the larger language models you are considering can be prohibitively expensive or otherwise technically impossible with your own computing resources. The Evaluation on the Hub tool we released this year can help with that: not only will it run the evaluations for you, but it will also help connect them to the model documentation so the results are available once and for all — so everyone can see, for example, that size measurably increases bias risks in models like OPT!

For models just as for datasets, different tools for documentation and evaluation will provide different views of bias risks in a model which all have a part to play in helping developers choose, develop, or understand ML systems.

- Visualize

- Generative model: visualize how the model’s outputs may reflect stereotypes

- Classification model: visualize model errors to identify failure modes that could lead to disparate performance

- Evaluate

- When possible, evaluate models on relevant benchmarks

- Document

- Share your learnings from visualization and qualitative evaluation

- Report your model’s disaggregated performance and results on applicable fairness benchmarks

As we learn to leverage ML systems in more and more applications, reaping their benefits equitably will depend on our ability to actively mitigate the risks of bias-related harms associated with the technology. While there is no single answer to the question of how this should best be done in any possible setting, we can support each other in this effort by sharing lessons, tools, and methodologies to mitigate and document those risks. The present blog post outlines some of the ways Hugging Face team members have addressed this question of bias along with supporting tools, we hope that you will find them helpful and encourage you to develop and share your own!

Summary of linked tools:

- Tasks:

- Explore our directory of ML Tasks to understand what technical framings and resources are available to choose from

- Use tools to explore the full development lifecycle of specific tasks

- Datasets:

- Make use of and contribute to Dataset Cards to share relevant insights on biases in datasets.

- Use Disaggregator to look for possible disparate performance

- Look at aggregated measurements of your dataset including nPMI to surface possible stereotypical associations

- Models:

- Make use of and contribute to Model Cards to share relevant insights on biases in models.

- Use Interactive Model Cards to visualize performance discrepancies

- Look at systematic model errors and look out for known social biases

- Use Evaluate and Evaluation on the Hub to explore language model biases including in large models

- Use a Text-to-image bias explorer to compare image generation models’ biases

- Compare LM models with Bias Score Card

Thanks for reading! 🤗

~ Yacine, on behalf of the Ethics and Society regulars

If you want to cite this blog post, please use the following:

@inproceedings{hf_ethics_soc_blog_2,

author = {Yacine Jernite and

Alexandra Sasha Luccioni and

Irene Solaiman and

Giada Pistilli and

Nathan Lambert and

Ezi Ozoani and

Brigitte Toussignant and

Margaret Mitchell},

title = {Hugging Face Ethics and Society Newsletter 2: Let's Talk about Bias!},

booktitle = {Hugging Face Blog},

year = {2022},

url = {https://doi.org/10.57967/hf/0214},

doi = {10.57967/hf/0214}

}