Wireframing is a practice used by UX designers which allows them to define and plan the information hierarchy of their design for a website, app, or product. This process focuses on how the designer or client wants the user to process information on a site, based on the user research already performed by the UX design team.

When designing for the screen you need to know where all the information is going to go in plain black and white diagrams before building anything with code. Wireframing is also a great way of getting to know how a user interacts with your interface, through the positioning of buttons and menus on the diagrams.

Without the distractions of colors, typeface choices or text, wireframing lets you plan the layout and interaction of your interface. A commonly-used argument for wireframing is that if a user doesn’t know where to go on a plain hand-drawn diagram of your site page, then it is irrelevant what colors or fancy text eventually get used. A button or call to action needs to be clear to the user even it’s not brightly colored and flashing.

Before you start designing the wireframes of your own app or product, take a look at some examples of wireframes. This will give you some inspiration for your own wireframes, as well as giving you an idea of the variety of ways of creating them. Some people like to draw their wireframes by hand, others feel more comfortable using software like Invision, or Balsamiq to create theirs. We’ll go through some of the tools you can use to create wireframes shortly, but it’s important to emphasize that how you make yours is up to you: some people feel more creative when sat at their computer, while others prefer to have a pen and paper in hand.

That said, for complete beginners, bear in mind the following when deciding on your wireframe creation process:

Wireframes drawn with paper and a pencil, or at a whiteboard, have the advantage of looking and being very easy to change, which can help tremendously in early conversations about your website or product. With the help of paper-prototypes, you can test with end users at every stage of ideation and design. Changes at these stages are much easier—and therefore cheaper—than changes deemed necessary after coding is under way. Switching later to software (after initially hand-drawing your wireframe) allows you to keep track of more detailed decisions. It’s likely to be to your advantage to start off hand-drawing your wireframes before executing more detailed versions using an online app or software. The following wireframes should give you a good idea of how information can be organized on the screen.

Wireframes from CareerFoundry student Samuel Adaramola:

Remember: UX design is a process, and wireframing isn’t the first step in this process. Before you even think about picking up a pen and paper, you need to have covered the first two steps; namely understanding who your audience is by way of user research, detailing requirements, creating user personas and defining use cases, and complementing this with further competitor and industry research. What does that mean? That means carrying out analysis of similar product lines to your own, digging into prevailing UX trends and best practises, and, of course, reviewing your own internal design guidelines.

And if you’re designing a new feature, don’t be afraid to research outside of your domain. Introducing tracking and data visualization as part of your logistics company’s service? Perhaps it’s worth checking out some fitness or nutrition apps on Dribbble or Behance for some ideas. Creativity is often set loose at point where fields of expertise intersect, after all.

Unsure what user research is and why it’s very, very important? Let us explain.

You can imagine how much quantitative and qualitative data those various phases will produce. Well, that’s what you need to keep in mind while drawing out your wireframes. If you’re a mere mortal, you might struggle to both retain and recall all of that, so I recommend scribbling a cheatsheet with your business and user goals (your requirements), your personas, use cases, and perhaps some reminders of the coolest features you stumbled across in your competitor research. A few choice quotes from your audience might also help focus your attention on the user’s experience, which is—never forget—what you’re designing!

Your wireframing is going to get very messy very quickly if you don’t have an idea of how many screens you’ll need to produce and the flow you expect the user to follow. It’s important to have a watertight concept of where your users will be coming from (which marketing channel, for example, and off the back of what messaging), and where you need them to end up. If you’re already well-acquainted with UX vocabulary, your internal voice will be alternately screaming “user flows” and “information architecture”.

Good information architecture will ensure that your users are self-sufficient (fewer messages to your customer service asking how to do something painfully simple), lower levels of user frustration (and ultimately more satisfaction and trust), and therefore lower drop-off or drop-out rates. Which probably means more revenue, and probably means happy managers—and a job well done.

Don’t know what Information Architecture is? We’ve got that covered for you too.

A UX designer connecting paper wireframes into a user flow

Ok, now we’re on step four and you can finally start putting pen to paper. Sorry it’s taken this long, but the previous steps were critical: The old adage that you should look before you leap is 100% relevant to UX.

Anyway, let’s get some wires on your frame. Remember: you’re outlining and representing features and formats, not illustrating in mighty fine detail. There’s nothing worse than a blank piece of paper, so you need to start getting your ideas down pronto—that’s the imperative for step three. Don’t think about aesthetics, don’t think about colors—the UI designer can deal with that. And if you’re the only designer at your fledgling startup… well, just do it later.

A good, thick marker pen (a Sharpie, as our friends in the US call them) is a handy tool for this stage of wireframing. Why? Because it prevents you from drowning yourself in detail. You’ll focus on delineating the functional blocks that form the skeleton of your design. As Jeff suggests in the video above, pose yourself the following three questions while you’re sketching:

How can you organise the content to support your users’ goals? Which information should be most prominent? Where should your main message go? What should the user see first when arriving at the page? What will the user expect to see on certain areas of the page? Which buttons or touch points does the user need to complete the desired actions? Once you have a few variations of your first screens, you might want to do a bit of collaborative wireframing with a fellow designer or product manager. What’s that mean? Simple. Lift your wireframes off the paper and onto a whiteboard, and play around with them. Ask yourself and one another; “Are we creating something usable that meets our audience’s needs?”

So you have a flow and you have your screens, and you’ve corroborated your ideas with some clued-up colleagues. The next step is to add some informational details to prepare your wireframe for its upgrade, Megatron-style, to prototype-mode.

Add detail in the way you would naturally process a screen, or the page of a book: from top-to-bottom and left-to-right. Remember: Your wireframe is the skeleton of your site. You’re not adding the muscle just yet—the content and the copy. To extend the metaphor somewhat uncomfortably, these elements are the ligaments and tendons that will connect form and functionality. Think about the following:

Usability conventions, such as putting the navigation at the top next to your logo, having a search box on the top right, and so on Simple, instructional wording for i.e. calls-to-action Trust-building elements: What do you need to build trust in your customers and where would be the best place to put these elements? Tooltips to indicate any functionality that could be included in a prototype transition Once you’ve done all that, you’re ready for your first user tests. At this stage, your users may well be your colleagues. Indeed, one of the joys of the humble wireframe is that it serves as a common language between designers, stakeholders and web and app developers. You can use tools like UsabilityHub to preference test screens and collect qualitative feedback, and Prott to test and check understanding of the basic user flow. With this tool, you can simply photograph and upload your hand-sketched wireframes, and then connect them to user button overlays. Clever stuff!

Know nothing about Usability Testing? Here’s a guide for beginners.

Once you’ve documented and acted upon the feedback from your first prototype, you can start developing your high-fidelity prototypes. There are lots of slick tools out there for this, from Proto.io to Adobe XD and Framer, but the most well-known are Sketch and the browser-based, new(ish) kid-on-the-block, Figma. Once you’ve developed your wireframes in Sketch, you can import them into the industry-leading prototyping tool InVision (which, incidentally, we built a course in conjunction with) and interlink your screens for a second round of high-fidelity user testing. It’s at this point that we’ve most certainly crossed from wireframing to prototyping. To find out more about that, you’ll have to read another article.

Let’s summarize by reviewing three key principles to keep in mind when you’re producing your wireframe.

The following points should be at the forefront of your mind when building your wireframe:

-

Clarity Your wireframe needs to answer the questions of what that site page is, what the user can do there, and if it satisfies their needs. Your wireframe is an aid for you to visualize the layout of your site page and ensure that the user’s most important questions are answered and goals are achievable without being distracted by more aesthetic considerations.

-

Confidence Ease of navigation through your site and clear calls-to-action increase user confidence in your brand. If your site page is unpredictable, or has buttons or boxes in unexpected places user confidence diminishes. A lot of this information can already be organized at the wireframing stage. Using familiar navigational processes and placing buttons in commonly-used and intuitive positions, user confidence will soar–and that’s before you’ve even gotten around to thinking about colors and styles.

-

Simplicity is key Too much information, copy, or links, can be distracting to the user and will have a detrimental affect on your users’ ability to achieve their goals. You want your users to be able to find their way through your site with as little extra ‘fluff’ as possible, to the elements that map to their most significant goals in a given context.

Your wireframe should be a visual guide to the framework of your site and how it will be navigated. Attractiveness at this stage is not a consideration. Once you’ve decided who your product or service is for, you can begin laying out the information they are looking for in an intuitive and natural way that is not only familiar to them as users of this kind of service, but that also guides them towards the conversion point or otherwise helps them to achieve their goals in the interaction. By presenting your information in this way, you are aligning both the business goals of your site with the needs of the customer.

Further Resources If you’re just starting out in the world of wireframes and UX design, I highly recommend taking a look at the following articles.

What’s The Difference Between A Wireframe, A Prototype And A Mockup? How Does Wireframing For Websites And Mobile Apps Differ? The Wireframing Tools Every UX Designer Should Know Workshop Recording: An Introduction To Wieframing in Sketch

Previous Overview: Getting started with the web Next HTML (Hypertext Markup Language) is the code that is used to structure a web page and its content. For example, content could be structured within a set of paragraphs, a list of bulleted points, or using images and data tables. As the title suggests, this article will give you a basic understanding of HTML and its functions.

HTML is a markup language that defines the structure of your content. HTML consists of a series of elements, which you use to enclose, or wrap, different parts of the content to make it appear a certain way, or act a certain way. The enclosing tags can make a word or image hyperlink to somewhere else, can italicize words, can make the font bigger or smaller, and so on. For example, take the following line of content:

My cat is very grumpy If we wanted the line to stand by itself, we could specify that it is a paragraph by enclosing it in paragraph tags:

My cat is very grumpy

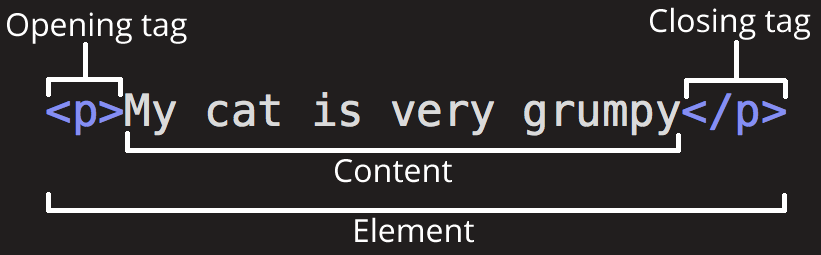

Copy to Clipboard Anatomy of an HTML element Let's explore this paragraph element a bit further.The main parts of our element are as follows:

The opening tag: This consists of the name of the element (in this case, p), wrapped in opening and closing angle brackets. This states where the element begins or starts to take effect — in this case where the paragraph begins. The closing tag: This is the same as the opening tag, except that it includes a forward slash before the element name. This states where the element ends — in this case where the paragraph ends. Failing to add a closing tag is one of the standard beginner errors and can lead to strange results. The content: This is the content of the element, which in this case, is just text. The element: The opening tag, the closing tag, and the content together comprise the element. Elements can also have attributes that look like the following:

Attributes contain extra information about the element that you don't want to appear in the actual content. Here, class is the attribute name and editor-note is the attribute value. The class attribute allows you to give the element a non-unique identifier that can be used to target it (and any other elements with the same class value) with style information and other things.

An attribute should always have the following:

A space between it and the element name (or the previous attribute, if the element already has one or more attributes). The attribute name followed by an equal sign. The attribute value wrapped by opening and closing quotation marks. Note: Simple attribute values that don't contain ASCII whitespace (or any of the characters " ' ` = < > ) can remain unquoted, but it is recommended that you quote all attribute values, as it makes the code more consistent and understandable.

Nesting elements You can put elements inside other elements too — this is called nesting. If we wanted to state that our cat is very grumpy, we could wrap the word "very" in a element, which means that the word is to be strongly emphasized:

My cat is very grumpy.

Copy to Clipboard You do however need to make sure that your elements are properly nested. In the example above, we opened theelement first, then the element; therefore, we have to close the element first, then the

element. The following is incorrect:

My cat is very grumpy.

Copy to Clipboard The elements have to open and close correctly so that they are clearly inside or outside one another. If they overlap as shown above, then your web browser will try to make the best guess at what you were trying to say, which can lead to unexpected results. So don't do it!Empty elements

Some elements have no content and are called empty elements. Take the element that we already have in our HTML page:

Anatomy of an HTML document That wraps up the basics of individual HTML elements, but they aren't handy on their own. Now we'll look at how individual elements are combined to form an entire HTML page. Let's revisit the code we put into our index.html example (which we first met in the Dealing with files article):

<title>My test page</title>